Zombie start-ups: On the same side

Zombie companies present a special challenge for VC investors, whose exit goals may not match the aims of the founders. Successful GPs will try to ensure a positive experience for all parties

As 2016 began, Grofers' stars seemed to have aligned. The Indian hyperlocal delivery start-up had just raised a $120 million Series C round led by SoftBank, with participation by existing backers Sequoia Capital and Tiger Global, which put it well ahead of its nearest rival BigBasket in total funds raised. In addition, a high-profile advertising campaign was showcasing the company to the young urban consumers it saw as its core user base.

But in the months following the round, the founders had grown increasingly worried. While order volumes were strong and revenue was growing, high operational costs meant the business was far from breaking even. Management suspected this weakness was inherent to the company's business model, which mainly aimed to enable delivery of small items from local shops to consumers.

"We were an impulse purchase for a consumer and not a planned purchase, so our ticket sizes would always be small. We took a call on what people really want, and realigned the entire organization to understand the consumer first," says Prashant Verma, director of marketing at Grofers. "Anything that we do today stems from the reality check that we had with ourselves in August 2016."

Grofers' reassessment led to a significant pivot. Rather than operating on a purely hyperlocal basis, the company shifted to a primarily inventory-based model, aiming to position itself as customers' main source for groceries and other daily goods. A pilot program in Gurgaon demonstrated the viability of the model, which has since been rolled out on a wider basis. Consumers have responded enthusiastically, with the company claiming sales revenue growth of more than 20% month-on-month since March.

Investors supported this reinvention, and many in the VC community say this type of self-directed change is what they want to see from a portfolio company facing sluggish growth. But often such actions are not taken, either because management fails to recognize the challenge ahead or sees it as a problem for investors rather than themselves.

In the worst cases, start-ups can develop into so-called zombies: companies that can stay in business, at least for a time, but offer little hope of recapturing growth and delivering positive exits to their backers. At such times investors must look for ways to safeguard their own interests and find a way to ensure an exit – even at the cost of their relationship with the founders.

Failure rates

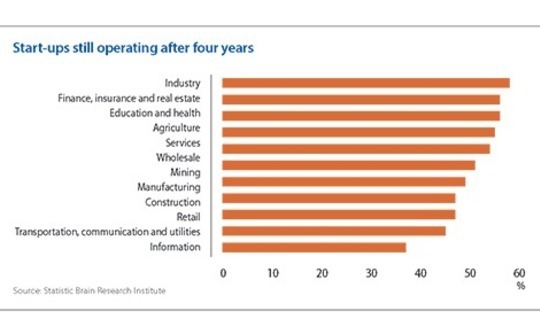

It is no secret that the majority of start-ups don't succeed. According to data compiled by Statistic Brain Research Institute, one in four start-ups in the US fail within the first year after founding, while another 25% will not survive after four years in operation. By year eight, two-thirds will have shut their doors.

Start-ups in the information sector are the most likely to close in the first four years, with Statistic Brain's figures showing only 37% of US information start-ups remaining open past this point. Companies in the finance, insurance and real estate sectors were most likely to stay open, at 58%, while education and health, agriculture, services, wholesale and mining all showed a survival rate of more than 50%.

"To a large extent we rely on the founders to make the judgment," says Tuck Lye Koh, co-founder and CEO of China-based Shunwei Capital Partners. "I've seen cases in which the founders get very creative and they come back with ideas for changing the business, and other cases where the founders say that this is not going anywhere. In extreme cases we've had founders ask to just liquidate the company."

Then there are zombies, in which founders continue forward on the same course despite low or stagnant growth, believing that applying a bit more effort to the original business model will deliver the results they are seeking. Investors see this status as the most challenging scenario.

In the VC community, two types of zombie start-up are commonly recognized. The first is a company that, while capable of continuing to operate for the near future, has no foreseeable chance of making a profit and will eventually need to fold without a fresh capital injection. The second type does make a profit and will likely continue to do so, but has failed to raise the interest of a potential acquirer.

Both are dangerous for a start-up's VC backers, because they are unlikely to lead to a resolution of the investment. Successful companies can command a high price at acquisition, while failing companies can at least be dissolved quickly when the entrepreneur recognizes the problem. But a zombie may hang on in an investor's portfolio for years, burning VC money or making its small profits while the fund nears the end of its life, bringing increasingly urgent demands for liquidity.

While all GPs are likely to have one or two such companies in their portfolios, Asia-focused investors say they have to guard against the phenomenon more closely. The same risk-averse cultures that make it difficult for locals to leave regular employment and form start-ups make those same founders reluctant to admit that their companies have gone as far as they can on the present course and should change direction or close down.

Investors' prospects for pushing zombie start-up founders onto a new course differ greatly depending on the situation. Ben Mathias, managing director and head of India for Vertex Ventures, has seen several zombie scenarios play out both at Vertex and at his previous firm New Enterprise Associates (NEA). In one case, a start-up operated a profitable line of in-vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics that propped up a cash-burning cosmetic surgery chain. Investors wanted the company to focus exclusively on the IVF business, but the founder resisted, claiming he could turn the cosmetic surgery line around.

"There was a lot of debate around the table on the strategy. But ultimately the people writing the checks could call the shots," says Mathias. "So this was a situation where the investors were putting in more money to gain leverage. And if the company hadn't needed to raise more capital, then the debate may not have been resolved."

Mathis did not have this advantage in another deal at NEA. The start-up, an SMS aggregator that helped companies advertise to consumers through mobile phones, had shown impressive growth during the holding period and achieved profitability. By any measure, it was a success. But its niche strategy had not captured the interest of larger players, the founder was happy keeping the company private rather than going for an IPO, and its VC investors were growing anxious about the direction of the business.

In the absence of a logical acquirer – an SMS aggregation business is not a good fit for most strategic players – NEA and its fellow investors pushed for a transition to a broader digital marketing approach. However, it was slow going to convince the founder that his successful business still needed to change – solely, it seemed, for the sake of its investors.

"The founder in this case was receptive and did try, but maybe he didn't try hard enough, because he didn't feel the pinch," Mathias adds. "Now, from what I see in the public domain they do seem to have made some success in pivoting. But it's been a long process to make that happen. The Series A investors have been in there for ten years now."

Losing alignment

What both cases have in common, and the fundamental source of difficulty for investors in the zombie start-up scenario, is that the founders saw their interests as fundamentally misaligned with those of their VC backers. In this event, industry players say investors need to be prepared with options that will allow them to assert their rights.

To a certain extent this protection can be built into the investment agreement through a guarantee that investors will be able to achieve an exit within a certain time frame. This can be achieved through a put option, in which founders or the company commit to buying back the investor's shares if a liquidity event has not been reached in an agreed-upon time frame.

Put options have been considered problematic in the case of underperforming start-ups, with industry professionals noting that companies facing operational difficulties are unlikely to have the resources to buy back stakes. In the case of a zombie this is less of an issue, since at this point the company typically is still healthy overall and can probably muster the capital for the buyback, while a founder who is not facing the pressures of a failing business can spare more attention for an investor's concerns.

Lawyers who have negotiated such deals acknowledge it can be difficult to get the agreement of founders, who may instead propose a drag right that allows investors to force a sale of the company. While this solution may be negotiated more quickly, the drawback is that it assumes an interested buyer, which may not be easy to find. Investors are better off insisting on a provision that keeps all guarantees between the two relevant parties.

"There is an essence of personal liability of the promoter that comes in, and that becomes sticky, because most promoters try to push back on anything involving personal liability," says Vinayak Burman, managing partner at boutique Indian law firm Vertices Partners. "However, if one is able to negotiate such rights then one has a certain amount of leverage through contractual mechanisms and can structure it whereby the promoter buys out partially to provide some immediate liquidity, and the company then buys out the rest subject to the relevant requirements of buy-back under the law. Typically, a waterfall mechanism is sought by the promoters as a negotiation pointer to create a breather."

However, such legal protections are not in themselves a perfect solution to the zombie start-up scenario. While they do offer a guaranteed exit opportunity that can generate a feeling of security, investors may be reluctant to take advantage of them in practice.

There are several reasons for this: for one, enforcement is not always straightforward. If founders decide to fight the VC backer, the investor may have to take them to court – which can be a significant drain on time and capital, even in markets like India and China where legal professionals say the efficiency of the court systems have improved in recent years.

Along with this practical reason, VC investors are often slow to implement their contractual rights for philosophical reasons. A founder whose start-up has entered zombie status most likely already believes his investors' interests don't align with his, and attempting to enforce a put option is only going to confirm that impression.

Nevertheless, most VCs prefer to find an exit scenario that benefits both themselves and the founders, if only to avoid becoming known as investors that work against the interests of their portfolio companies. In addition, ignoring a founder's wishes is unlikely to help a GP's exit process, and far more likely to slow down or even freeze it.

"If you force an exit, then you lose the cooperation of the founder, and it becomes that much more difficult to sell the company," says Vertex's Mathias. "Any buyer would want to interact with the management team to understand the company in more detail, and the person running the company would need to cooperate with that process."

In some cases, investors find that it is actually beneficial to remind portfolio companies at the beginning that their interests will not always be the same. The purpose is not to intimidate the founder, but rather to make sure that both sides understand each other and the reason why certain actions need to be undertaken.

"I've met VCs in Silicon Valley that tell me every time they do an investment they take the CEO off to the side and say, ‘This is what our interest is: we expect to see increases in the company's valuation, and raising money every two years. And if that doesn't happen we reserve the right to remove you as CEO,'" says Vinnie Lauria, founding partner at Golden Gate Ventures.

This is the kind of understanding that Golden Gate wants in its investments. The firm seeks to reassure founders that while it has its own obligations as a fund manager, it is committed to pursuing them in a way that works to the portfolio companies' advantage as much as possible. This means that when the investor needs to make an exit the founder understands its objectives and can help facilitate it from his end.

Acqui-hire option

If it is not possible to recover the investment through a sale to another investor or a share buyback by the founder, Golden Gate will pursue some form of acquisition instead. Often this takes the form of an acqui-hire, when a promising team at one company joins another without transferring the company's assets. Other times the opposite occurs, with the buyer taking on the assets of the company and the employees separating. In the case of Taiwan-based Popapp it was a combined of both, with the intellectual property sold to one competitor and the team hired by another.

This scenario is growing in popularity among investors who find it far preferable to simply giving up on a company and letting it fail. It does not give them an immediate exit, but they can often obtain a stake in the acquiring company which gives them an option for liquidity down the line, while arranging for the future of their portfolio company's assets and personnel. Though founders initially viewed the idea with reluctance, as the model spreads they have also largely come to appreciate its potential.

"I think one reason people were afraid of it was because it hadn't happened before locally. There weren't other examples that you could point to," says Lauria. "Now that's changed, there've been dozens of acqui-hires in Southeast Asia. There are a lot of examples that people can point to and say I feel comfortable doing this."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.