Hong Kong tech IPOs: Compromise solution

Hong Kong wants to reinvest itself as a destination for Chinese technology listings with a new board that would be open to companies that are pre-profit and have dual-class share structures. Will it fly?

Meitu is best known for an image-enhancing app that allows users to touch up selfies by enlarging their eyes and erasing their pimples. But the Chinese start-up attracted attention in financial circles last year by choosing Hong Kong over the US as the destination for its offshore IPO. It raised HK$4.88 billion ($629 million) in what was the largest internet offering on the exchange since Tencent Holdings in 2004.

Meitu's rationale was twofold. First, it expected a better valuation in Hong Kong than the US because local investors are more familiar with its products (the stock is trading at a 10% premium to the IPO price, valuing the company at HK$39.8 billion). Second, it sees long-term benefits in the Hong Kong-Shenzhen Stock Connect scheme, which makes it easier for mainland Chinese to buy Hong Kong stocks.

"We are constantly reviewing listing options for portfolio companies, and after Meitu, interest in Hong Kong as a hub for large tech companies is rising," says J.P. Gan, a managing partner at Qiming Venture Partners, one of several VC investors in Meitu. "Tencent's share price has jumped a lot because of its revenue and because of policy support – mainland Chinese like to buy Tencent instead of A-share listed companies. If more tech companies list in Hong Kong, I think they will also become popular."

Several young but relatively large Chinese tech companies, including financial technology player Lufax and online insurer Zhong An, are said to be targeting Hong Kong IPOs, having previously explored US and A-share listings.

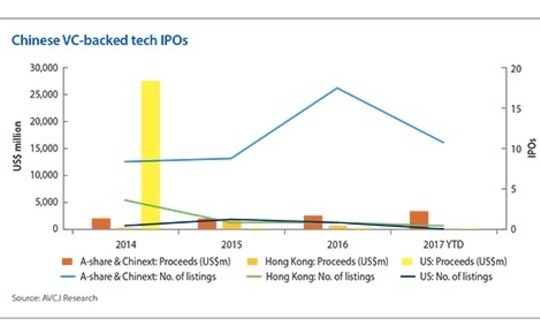

Although Hong Kong remains one of the world's leading markets for IPOs, with $25 billion raised last year, it has struggled to attract emerging technology companies due to its stringent listing requirements. Keen to capitalize on a booming sector, Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing (HKEx) will publish a consultation paper this month on establishing a new board with a compliance regime more suited to start-ups.

Its success is contingent on making allowances in two areas where the bourse has previously held firm: allowing listings by companies that are pre-profit and have non-standard voting rights structures.

The status quo

Under the current listing rules, unprofitable companies – including technology plays – with sufficient revenue are permitted to list on the Main Board. If an applicant has reported revenue of more than HK$500 million ($64 million) for the previous year, it can get a waiver for the net profit test. In Meitu's case, although it made a loss of RMB2.22 million ($326 million) in 2015, the company was still eligible for a main board listing because its revenue came to $107 million, up 52% year-on-year.

"I think the companies that could list on the new board would have neither profits nor revenues, or those that feel adamant about adopting a dual-class share structure. Those will be the key new things," says Christopher Betts, a Hong Kong-based partner at law firm Skadden.

Dual-class structures – where different classes of shares have distinct voting rights and dividend payments – became an issue of contention when Alibaba Group favored New York over Hong Kong for its $25 billion IPO in 2014.

The Chinese e-commerce giant lobbied Hong Kong regulators to permit a bespoke structure that consolidated power within a group of 28 partners – giving them control of the board even though their combined post-listing equity stake would be only 10% – but to no avail. The structure was at odds with HKEx's traditional "one share one vote" system, which favors majority shareholders.

The Securities and Futures Commissions (SFC) then turned down HKEx's call for a public consultation on dual-class listing structures, saying investor protection measures were insufficient. HKEx responded by proposing a new technology-focused board that would operate separately from the main board and the Growth Enterprise Market. This time the SFC supported a formal public consultation on the matter.

"Charles [Charles Li, HKEx's CEO] just felt bad about losing Alibaba. I don't think the launch of the new board with new initiatives is because HKEx has got a bunch of tech companies lining up in front of their door, saying ‘If you don't give me a dual-class share structure, we're not going to list here,'" a legal practitioner says.

"Without a dual-class listing structure, these founders' shares will be further diluted and they may not be able to control the company after going public," says Gary Ngan, Meitu's CFO. "Management control is arguably less important once a company is large and stable, but in the early stages, when it is still taking a lot of risks to invest in growth, direction from founders can be very important."

Meitu didn't ask for a dual-class share structure because it has managed to build up a base of more than one billion users without burning much cash on sales and marketing. In other words, there had been no need to raise multiple rounds of pre-IPO funding, with the volume of new shares issued large enough to dilute the founder to a minority position once the public offering is completed.

However, Ngan notes that Meitu is "a very rare case in the tech space" as many large Chinese companies – in particular in the online-to-offline space – require substantial amounts of third-party capital to gain market share prior to monetization. In those cases, a dual-class structure is essential if the founder is to remain in control.

Effective gatekeepers

In addition to easing financial requirements and permitting flexible listing structures, HKEx's new board must feature a streamlined listing process if it is to attract technology companies. At present, a listing applicant for the main board must attend a hearing before HKEx's listing committee, which decides if the company is suitable for a listing. This judgment is often based on whether or not the committee thinks a business model is sustainable.

"A lot of pre-profit companies' business models are still evolving and they may have yet to achieve monetization or be trying different ways to optimize it. The exchange can't expect these companies to have sustainable business models on IPO – as has been required of listing applicants up until now – and it might not be in the best position to judge whether their business models will be successful or not," says Skadden's Betts.

HKEx might, therefore, consider replacing the subjective suitability for listing with a disclosure-based regime, much like that used in the US, under which applicants list all potential vulnerabilities in their business model and investors make their own decisions. Regulators will also need to establish a balanced approach to policing these companies. If a company abuses the dual-share structure process, there should be a mechanism to discourage or prevent future transgressions through enhanced enforcement or investigation processes and penalties, says Henry Ong, a partner at law firm Weil.

Implementing the new board would be a protracted process, and gathering sufficient momentum and credibility to attract Chinese technology companies would take longer still. As such, for a tech company with a near-term Hong Kong listing plan, the new board is not an option. But the very existence of the consultation paper is an indication that Hong Kong recognizes the existing regulatory framework is not suitable for all applicants, and it must be modified if the exchange is not to miss out on a golden opportunity.

"There are a lot of challenges but there should be a goal to try and create an ecosystem, or a separate universe, for these types of tech companies that don't have the track record or that look for alternative governance structures," says Ong. "For instance, there might be 100 Chinese unicorns eyeing NASDAQ or Hong Kong listings and, by not doing anything, Hong Kong has a high chance of losing quite a few of them. That's the reality."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.