Co-working spaces in Asia: Spaced out

Co-working spaces are proliferating in Asia as companies – from multinationals to start-ups – opt for more flexible real estate arrangements. The transition is real, but are the valuations justified?

"It's quite lonely for a start-up sometimes and there is great emotional value in having other people around you, at various stages of development, also doing their own entrepreneurship thing," says Marc Hardy, CEO and co-founder of RunSocial, which has developed video software capable – on screen, at least – of taking the runner off the treadmill and onto undulating hills in Tuscany.

The company incorporated in Singapore about three years ago and Hardy has seen or experienced a number of different co-working spaces. Last November he took up residence in Collision 8, a relatively high-end operation that had opened a few months earlier. One of the selling points was the appealing layout and décor. "It's a classy environment, I'd rather be there than in a Starbucks," Hardy says.

For around S$600 ($433) a month, he gets unlimited 24-hour access to the premises – on a hot-desking basis – plus use of meeting rooms, Wi-Fi, mail management, and snacks and beverages. Members are also invited to various networking events. These services are not unlike those offered by other providers, but Hardy compares selecting a co-working space to buying a watch: with different models even in terms of functionality, it comes down to an element of personal style.

While there is a cost consideration – user contracts last for months, offering more flexibility than multi-year leases on a permanent space – people make the difference. The environment is friendly but not just-graduated-from-university raucous, and Hardy has made connections with potential business partners and bought services provided by other members.

HackerspaceSG, which launched in 2009, has the distinction of being Singapore's first co-working space. Collision 8 will certainly not be the last. From the ubiquitous WeWork to traditional serviced office providers to all manner of local property developers, the market is becoming increasingly saturated. And similar scenarios are playing out in leading cities across Asia, prompting questions about the balance between demand and supply.

"Co-working is about finding a tribe – you are part of a community," says Hugh Mason, who co-founded HackerspaceSG before going on to launch accelerator JFDI.Asia. "There are some people who really get that but then all these real estate guys came in with a rent-seeking mindset. We are at the absolute peak of the hype cycle right now. People start off naively thinking they can just sell desks and chairs, but then they get into a price war and they have two choices: go bust or get inventive."

Social experiments

Depending on whom you ask, co-working spaces originated with freelancers gathering around kitchen tables in the US or London gentlemen's clubs that grew into business clubs in the 1980s. It may well be a bit of both, but the common theme is social activity morphing into commercial activity, based on the desire of like-minded people to work together. The community was there before the real estate.

Co-working became a real estate play, rooted in economic necessity, with the emergence of Regus and Servecorp, pioneers of the serviced office and virtual office models. These concepts took on renewed importance in the wake of the global financial crisis as cost-conscious corporations decided it was better to house some staff in outsourced premises as required than carry underutilized property inventory.

It is really only in the industry's most recent developmental wave that community and real estate have fused in a way that can deliver scale – an evolution driven by technology-enabled mobility, the agglomeration of entrepreneurial young people, the emergence of the sharing economy, and government support for innovation. "We've always had space. What's different this time is putting people first, the human experience," says Megan Walters, head of research for Asia Pacific at JLL.

Real estate developers are responding to these trends. In China, for example, CITIC Capital has allocated part of its Shanghai Lane 189 shopping mall for a co-working space, which will be operated by local specialist naked Hub. The property investor recognized that attracting retailers is difficult, particularly when trying to fill the higher floors of developments; it therefore made sense to put the space to another use. But naked Hub is expected to contribute to the broader success of Shanghai Lane 189.

"Naked Hub clients are likely to be start-ups with young people who want to enjoy lifestyle services. That is a good fit for our mall. A few hundred young people will be coming to the mall every day, using the services and drawing traffic up to the sixth and seventh floors," says Stanley Ching, managing partner for real estate and senior managing director at CITIC. "It is fantastic for us and convenient for them."

While many co-working spaces are – or claim to be – oriented towards start-ups, that is not the only user profile. Members could also be employees of small but established companies that prioritize the convenience of these services over the desire to interact with others, or multinationals providing flexible workspace solutions for staff and simultaneously exposing them to innovative environments.

Last year, HSBC announced that it would rent 400 hot desk positions at one of WeWork's Hong Kong properties. It was seen as a cost-saving measure, but also a means of enabling employees to collaborate with like-minded teams outside the bank. In the US, mobile operator Verizon Communications took this a step further, creating co-working spaces in its own premises and opening them up to clients. Occupancy by Verizon employees is capped at 10% to encourage interaction with third parties.

It has got to the point where groups are entering the market because they feel they must. They include real estate developers that fear big corporations are moving inexorably towards shorter-term, more flexible space, which could herald a structural change within the industry and erode the value of traditional long-term leases. However, these bold moves by developers are not necessarily insightful.

"I don't think the people jumping in right now are clear on what they are doing and why are doing it," says Peter Andrew, head of workspace strategies for Asia Pacific at CBRE. "There is a knee-jerk response from some of the developers, while others who do understand it are bringing in concepts from other places. It's the formative stage of an industry where people are experimenting with things."

Expansion by numbers

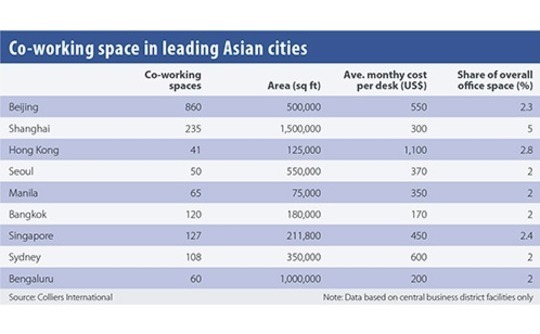

Colliers International pegged the number of co-working spaces in 12 leading cities across Asia Pacific at nearly 1,700 at the end of last year, with total floor space of 4.8 million sq ft. The build-out has been particularly visible in China, with Beijing and Shanghai hosting more than 1,000 spaces between them. Hong Kong represents the top end of the market: 41 centers and an average monthly cost per desk of $1,100. This compares to 127 centers and $450 per desk in Singapore.

While co-working space operators have traditionally opted for spaces of 10,000 sq ft or below, the market is increasingly dominated by large projects. WeWork opened two spaces in Hong Kong last year covering 150,000 sq ft, while naked Hub is about to launch a 60,000 sq ft center in the city. In Shanghai, WeWork, UrWork, naked Hub and The Executive Centre (TEC) opened four spaces with a combined area of 250,000 sq ft, while JustCo and Regus added 130,000 sq ft across three facilities in Singapore.

Since then, WeWork has received $300 million from SoftBank at a reported valuation of $17 billion. The company has suggested that the key drivers of its business – urbanization, sharing of space and services, the rise of entrepreneurial millennials – justify this number and that those who claim there is a valuation bubble are failing to take into account the weight of industry momentum. Not everyone buys into this, seeing it as symptomatic of the hype behind most PE and VC investments in the space.

"We are valued at $400-450 million, or an EBITDA multiple of 10-12x earnings. It is inexplicable to me how WeWork is not a serviced office business valued at 10-12x – it rents floors and puts in lounges and glass-box offices – but a technology company valued at 160x," says Paul Salnikow, founder and CEO of TEC. "We've led with the network and the profitability of the business and we are valued on a traditional basis. This operator is promoted as something else."

TEC, which counts HPEF Capital Partners and CVC Capital Partners as its backers, is the fourth-largest serviced office provider globally, with 101 premium locations across 27 cities in Asia Pacific. It has been around for more than 20 years and is seen as a traditional player, but Salnikow argues that the product offering is not that different from WeWork: both offer attractive space and services, with members able to communicate with one another through dedicated apps.

What WeWork has done more effectively than others is recognize the importance of branding. Walters of JLL compares the dynamic to the appeal of London's Bond Street, Tokyo's Ginza and New York's Fifth Avenue in the world of traditional retail: everyone knows the names and what they stand for, and so they gravitate to these locations in search of a particular environment. Once this is established in users' minds, picking WeWork over Regus is like booking Uber Pool rather than queuing for a taxi.

Joe Seunghyun Cho, chairman of Marvelstone Group and CEO of Lattice80, a dedicated financial technology co-working space in the city, credits WeWork with "turning a property play into a tech company" and delivering improved profit margins as a result. What has yet to be established is whether it and others can continue to provide the kind of experience users expect when operating at scale in multiple markets, and facing ever intensifying competition.

Set up to survive?

Few industry participants dispute that major cities are at or have surpassed the point of oversupply, but everyone has an explanation as to why it doesn't impact them. Marvelstone opened Lattice80 as recently as six months ago and Cho expects at least five co-working spaces to open over the next six months in the very same building. "We don't see any competition," he says. "We have the community and the branding."

Similarly, Jonathan Seliger, CEO of naked Hub, notes that smaller operators are already going out of business in China because they can't sustain the discounts that must be offered to attract occupants. But he believes naked Hub is positioned differently to the mass-market bums-on-seats brigade, placing more emphasis on unique locations and design as well as creating an authentic and engaged community.

Naked Hub's latest innovation is the "naked angels," an executive assistant service that can do everything from book plane tickets to arrange simultaneous translation for a business presentation. The value-added services offered by co-working spaces range from whisky bars to warm cookies to events featuring relevant speakers, but the general objective is to make it easier for users to do business and make connections – thereby helping justify the premium they pay for access.

The challenge is execution: finding and furnishing a space is the easy part; an operator then has to attract members and keep attracting them, because co-working tends to generate very fluid revenue streams as people sign up for a few months and then move on; on top of that, the operator must replicate the model in each new location. At the heart of these retention efforts is creating and sustaining a community to which the target users want to belong.

According to Mason of JFDI.Asia, community building is about people, not real estate. "When we set up HackerspaceSG, we decided that physical space was important. Entrepreneurship involves taking risks despite enormous failure rates – it is like a faith and every faith has places where people can come together," he says. "But you can run it from any space; we could have run JFDI out of a Starbucks."

Drawing comparisons between accelerators and co-working spaces is flawed because of this community element. An accelerator program is a 100-day process, with everyone starting from the same point and working towards a defined end, which is usually raising capital. Shared experience is ingrained in that process. Members of a co-working space are not aligned around a single objective. They have different needs and objectives, which makes it harder to find common ground beyond the space they are sharing.

The counterargument is that co-working spaces flourish because of their diversification, but there are still plenty of operators pursuing differentiation through specialization. Lattice80 is a case in point. The model is predicated on fintech enterprises having a particular need for strong relationships with regulators and access to capital. Events are therefore intended to help establish these touchpoints and one of the largest tenants in the space is accelerator Startupbootcamp FinTech Singapore.

Other providers have gone so far as to bring the incubation element in house, creating a permanent link between real estate provider and capital source. Last month, UrWork – which runs more than 80 centers across 22 Chinese cities and has made forays overseas – agreed to merge with smaller industry peer New Space in order to differentiate its business. Both companies have received substantial VC backing. While UrWork is a pure-play co-working space operator, New Space also serves as an incubator.

"We have our respective niches and we thought it was time for us to merge and provide young entrepreneurs with more services, and maximize our value," says Josh Zhang, chief strategy officer at UrWork. "We think the industry is entering a new phase, and following the merger, we can create a new standard model."

Impact Hub, a Singapore-based operator founded in 2012, has taken a similar path, launching an in-house venture fund that will back start-ups using the co-working space. Grace Sai, co-founder of Impact Hub, sees it as a natural extension of a product offering specifically designed to support entrepreneurship.

"For us, it started by wanting to provide a supportive community for entrepreneurs who want to forge their own path. We have since seen how peer learning and networking helps start-ups – it is all about lengthening their runways by increasing their chance of success," she says. As such, Impact Hub measures its own success in terms of bump rates – people running into each other serendipitously – as well as intentional connections made for members. Team performance is partially tied to these metrics.

Predicting the future

Not all co-working space operators will follow this course. One feasible outcome envisages the industry diverging, with a handful of global players at one end of the scale and smaller specialists at the other. The former would largely rely on multinationals as anchor tenants. For example, a company renegotiates its lease so it has less fixed floor area but access to co-working spaces owned by the real estate developer – and operated by a third party – at multiple properties. The latter would focus more on start-ups and small businesses.

However, there are two obstacles to development. First, cross-border expansion is a priority for many operators, but it remains to be seen how effectively they adapt to local habits. A standardized offering makes sense in that a globe-trotting individual can expect the same level of service wherever he goes, but there will be differences in what Chinese and US entrepreneurs want from a co-working space. This may only become apparent as large-scale players move beyond major urban centers.

For example, the Deskmag survey found that open workspaces, though still the dominant format globally, have fallen gradually in the last three years, with more people opting to use offices on an individual or a team basis. Various industry participants question whether open workspaces are an appropriate format for China at all. UrWork's Zhang warns that "If you take a one-size-fits-all approach, you will fail," noting that glass-partitioned offices are more likely to be found in second-tier cities.

Jeffrey Li, managing partner at Tencent Investment, adds: "We have studied WeWork's business model and there is still a huge gap between China and the US. It is hard to identify anyone with the potential to build a sizable business in China. This relates to the operational model, cost structure and people's acceptance to this kind of co-working environment."

Cultural differences can be addressed over time, but the second issue is more immediate: How does the industry respond to a downturn? Real estate developers that targeted co-working on an opportunistic basis and offer plain vanilla products, would make a rapid exit, reallocating space to other uses. For operators that have cultivated a local or global brand name, demand might be more robust, but the sustainability of their expansion initiatives will be put to the test.

Much rests on the fortunes of WeWork. Should the company go public in the next 12 months – many think it will try – and investors respond positively, then it would set a benchmark for all other investments in the industry. The technology-enabled story would effectively be underwritten. Should its performance waver, the reset everyone is waiting for would be more painful and wide-ranging.

"Having exploded in everyone's awareness and drawn in a lot of investment, the industry in many markets is oversupplied, rates are dropping and we are going to have a shake out much sooner than we are going to have our next high," says TEC's Salnikow. "Co-working will still be there 5-10 years down the road and it will have a larger market share, but we will have a downturn between then and now."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.