One Belt One Road: Critical mass

One Belt One Road aims to recast two continents’ worth of disconnected developing markets as a global economic nucleus. It is a geopolitical watershed with deep and complex investment potential

When an emerging markets investment vehicle targets a corpus of $15 billion, the sum is generally not considered a mere drop in the bucket. Then again, most ventures of this kind don't pursue a mandate that spans 5,000 miles and four billion people.

China Minsheng Investment Group's (CMIG) new Asian Institutional Investor Joint Overseas Investment Fund is aiming to raise this amount for projects related to One Belt One Road (OBOR), a Chinese government trade policy announced in 2013 that combines the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The fund is the latest in a growing list of large infrastructure capital pools being dwarfed by the enormity of the OBOR equation, but it has a plan to get the most bang for its buck.

CMIG will favor social infrastructure over physical industrial installations by partnering a range of asset managers with relevant niche competencies. The approach is notable because it not only plays to private equity's business development strengths, but also offers a holistic vision of OBOR that remains unfulfilled by the government-backed entities currently jumpstarting the initiative.

"Building a railway from A to B is great for all the people in that value chain, but we're looking beyond the assets themselves to the other industries that can benefit from the build-up," says Lawrence Chu, managing partner at BlackPine Private Equity Partners, one of the GPs partnering the CMIG fund. "We're focused on setting up infrastructure to drive growth in domestic wealth and consumption, which is pivotal to the longer term prospects of Belt and Road because you can't just export goods without anyone there being able to buy them."

Skepticism about the bankability of OBOR usually frames it as a desperate attempt by China to vent excess industrial capacity as part of an effort to avoid an economic hard landing. Investors have noted this perspective, but appear increasingly confident that the social drivers behind the opportunity set reflect a transgenerational zeitgeist rather than a short-term policy maneuver.

Planetary proportions

The economic scope of OBOR is impossible to calculate and difficult to exaggerate, even in vague macro terms. Within a quarter of a century, the largest coordinated infrastructure program in history aims to connect more than half the world's population through new trade routes and realize Eurasia's long-theorized capacity for geostrategic dominance as the "world island."

The effort is intended to transform China's geographic neighbors from dependents into viable economic partners and export markets. McKinsey & Company predicts that, as a result of increased infrastructure investment, OBOR countries may account for 80% of annual global GDP growth by 2050, bringing three billion people into the middle class.

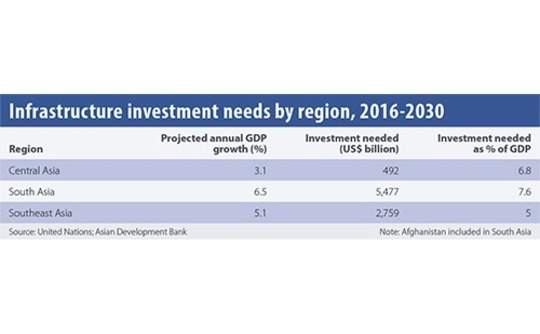

Even the short-term price tags for such a vision identify it as the biggest global story in the investment industry. The Chinese government has estimated some $5 trillion of financing will be required across the next five years. Over the next 10 years, Southeast Asia alone is expected to need about $2.5 trillion.

OBOR is too conceptual to be considered a master plan, however, and will therefore be ungovernable by China or even any multinational administration. It currently exists as a loose theme for soft dialogue between stakeholders in 64 countries hoping to establish project development ecosystems in their spheres of influence. In this context, investor participation may suffer from a lack of clarity around authority and alignment of interest – but it will also benefit from a diverse range of entry points.

"I'm not too scared that there are many fingers in the same pots at the same time because it stands to reason that the largest set of infrastructure investments in one geography that's ever been undertaken is not going to be clean and tidy," says Parag Khanna, international relations analyst and research fellow at National University of Singapore's Centre on Asia and Globalisation. "After all, you have a situation geopolitically where trust of China is at quite a low point. Despite that, China has been able to pull this off and rally the troops."

Geopolitically, OBOR has been widely interpreted as an instrument of Chinese hegemonic ambitions, or at its least assertive, a power balancing reaction to the proposed Trans Pacific Partnership. Nevertheless, diplomatic friction is not expected to impede investment since would-be regional challengers such as Russia and India are already heavily invested in the concept.

India, for example, is the second largest shareholder in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a Beijing-based multilateral financial institution launched in 2014 that is positioned to be one of the principal backers of OBOR projects. Russia is similarly swept up in the momentum, with the country said to have received more OBOR-related investment than any other jurisdiction so far at around $70 billion.

Most of this support has come from government-backed financial institutions and international multilateral investors. China Development Bank (CDB), China Investment Corporation, Export-Import Bank of China (Chexim) and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange established the $40 billion Silk Road Fund in 2014, and have made a combined initial commitment of $10 billion. Meanwhile, Shanghai's New Development Bank (NDB) launched in 2014 with $100 billion in capital focused on BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

In addition to AIIB – which also has $100 billion in capital – the European Bank for Reconstruction & Development, the World Bank and relevant domestic lenders such as the National Bank of Pakistan have demonstrated significant interest in participating. The current total of deployable OBOR capital from cross-border banks, however, is said to fall well short of the required $5 trillion at around $200 billion.

"The real bottleneck in Belt and Road is financing, but it's a problem that can't be solved by multilateral lending alone, and what's left is the private sector," says Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis. "Private equity and shadow capital into these Belt and Road countries will be a booming market, especially for projects that may have the likes of China Development Bank behind them."

The PE angle

One of the more active PE players in this space has been CITIC Capital, which began investing in China-Kazakhstan trade links in 2010 via its $200 million Kaznya Fund. When Kaznya finished its investment period last year, the firm launched the CITIC Capital Silk Road Fund, which is targeting up to $600 million for a broader mandate encompassing the breadth of OBOR geographies.

The vehicle has raised about half its planned corpus and is negotiating its first batch of deals. The plan is to leverage CITIC's Chinese connections across sectors including transport, logistics, energy generation and related utilities as well as food and water safety.

"We appreciate the advantage of transferable technology and products over the fixed assets per se," says Fanglu Wang, managing partner for the CITIC Capital Silk Road Fund. "For investments in intellectual property and applicable products, your scope may be potentially bigger than a fixed asset in terms of generating traction in multiple markets."

A focus on IP fits neatly into the view that private equity will find most of its inroads in infrastructure spin-off developments, downstream industries and supply chains. While specialized infrastructure funds are expected to integrate slowly into OBOR themes, the bulk of PE investors will seek more immediate exposure to supporting services across project management, raw materials, real estate, legal, accounting and security.

The need for modernization of these disciplines in OBOR countries is at the heart of the private equity opportunity. As various multi-state trade corridors begin to materialize, new professional standards and capacity requirements will drive increasing interest in outside capital with operational knowhow.

"We see it as an opportunity very much in line with the consumer and healthcare space," says John Lin, a partner at NDE Capital. "There is a shift in the supply chains between China and Southeast Asia that goes both ways, and if you break it down by value chain, there are a lot of gaps."

This strategy implies a ground-level involvement that is distinctly at odds with the high-altitude political power plays driving much of the heavy infrastructure investment so far. But private equity will need to align itself with more readily marketable business models in order to attract sufficiently diversified LP support and design deals with relatively early exit mechanisms.

"There are a lot of government-backed entities or funds involved in One Belt One Road, but because of their government nature, they tend not to be very commercial in their approach," says NDE's Lin. "We believe it is a better for private equity to get away from the restrictions of the G2G [government-to-government] approach."

For the moment, the public sector is still said to represent about 70% of infrastructure, and government interest remains essential as a means of creating an attractive environment for foreign investment. Southeast Asia – with a stronger reputation for legislating adequate procurement guidelines and public-private partnership (PPP) frameworks – may therefore benefit from an initial development advantage versus less stable OBOR regions.

Investors leveraging this backdrop include China-ASEAN Investment Cooperation Fund (CAF), a Chinese government and Chexim-backed PE vehicle pursuing an independent, commercially minded approach. It is targeting $10 billion for investments across the infrastructure spectrum, including heavy assets, social industries and "soft-infra" businesses such as logistics.

"Some Southeast Asian countries have some catching up to do in governance and accountability, but on the whole, I'd say ASEAN is more developed than a lot of other One Belt One Road areas such as Central Asia," says Partick Ip, a principal at CAF. "From a regulatory perspective, the biggest issues are foreign ownership and implementing PPP mechanisms."

The plausibility of any particular OBOR investment, however, may have less to do with the region of focus than whether the targeted project spans multiple jurisdictions. Although the bulk of financing will be bilateral – either China outbound investment or between any pair of governments – many projects will be contained within a single country and consequently benefit from a simplified growth trajectory.

"Projects that are self-contained and country-specific are more likely to be successful in securing funding in the short term, particularly if they come with a G2G wrap, which will make it easier for investments to come to fruition across various countries," says Will Myles, regional managing director Asia Pacific at Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS). "In cross-border projects with multiple governments and national jurisdictions and coming into the picture, it quickly becomes a series of G2Gs - or multilateral deals – which creates a lot more complications for investors."

An early example of a single-country OBOR project benefiting from this effect occurred in March, when Pakistan's Karot hydroelectric power project secured a $1.4 billion facility from CDB, Chexim, Silk Road Fund and the International Finance Corporation (IFC). The deal was touted as the first infrastructure deal under OBOR, but is also considered a natural extension of the existing China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

CPEC was formally established in 2015 as a continuation of an infrastructure cooperation agenda between the two countries that traces back to the end of the Sino-Indian War in the 1960s and includes major projects like the Karakoram highway network. Likewise, OBOR precursors in Southeast Asia include the Kunming-Singapore railway, which has a sporadic century-long history of development.

The question presented by these earlier cross-border corridors is whether use of the OBOR label in ongoing pan-Asian infrastructure development brings any meaningful new value to the proceedings. To its credit, OBOR appears to have clarified the rationale behind redrawing global trade flows for investors outside Asia. But the mantra and the brand are not one in the same. OBOR will have to establish enforceable procedural standards to maintain credibility.

"One of the challenges the Chinese government faces is the potential dilution of the brand because what they don't want is every project in any market in the 64 countries calling itself a One Belt One Road project," says Chris Brooke, managing director at consulting firm Brooke Husband and non-executive chairman for Asia Pacific at RICS. "Defining what constitutes a strategic project under the initiative is quite important and something investors will need to be careful about going forward."

Many of the regulatory and procurement challenges associated with OBOR are familiar to private sector investors that work in emerging economies but may be aggravated by the initiative's inherent cross-border flavor. As a result, technical project-level professional standards, in particular, may be an important stumbling block.

"Getting consistency in project appraisals and in assessing bankability – based on international standards in valuation, measurement and ethics – is both the challenge and the opportunity," says RICS's Myles. "The key question is to what extent you are willing to commit your cash to large-scale multi-jurisdictional, game-changing infrastructure projects which require decades-long obligations, if you don't have certainty on how to interpret what you're being told on paper."

Learning the ropes

The call for consistency is opening doors for the professional services industry, and Hong Kong is often mooted as a potential OBOR support hub given its experience helping usher China into the world economy. Hong Kong has been something of a forgotten actor in multilateral lending after failing to secure a base for any of the new OBOR-facing institutions including AIIB and NDB. However, the city may play a key role in confirming the investment merits of OBOR by providing much needed services around environmental, social and governance guidance – an area AIIB has emphasized would be a core priority.

Industry lobbyists cite a local capacity to provide offshore dispute arbitration and develop new products to cover private insurance or sovereign risk for OBOR investors, as well as a diversified fundraising market and cross-border banking advantages that can mitigate China's outbound capital restrictions. Hong Kong's emerging markets experience, meanwhile, could prove useful in managing the perception issues that continue to hamper engagement from Western investors.

"When it comes to infrastructure investment, misinformation exists about the risks in emerging markets and there's a need to bridge that information gap if countries are going to be successful in attracting private capital investment for OBOR project financing," says Ben Way, CEO of Macquarie Group Asia and co-head of Macquarie Infrastructure and Real Assets in Asia-Pacific. "Certain long-term investors may not be comfortable assuming risks associated with OBOR projects, so it may be necessary to either source specific capital from investors well-versed in the risks of developing economies, or adjust the risk allocation on these projects through negotiation with government."

This is where experienced infrastructure managers and civic administrators can assist investors targeting ancillary sectors. While the OBOR brand has successfully raised awareness about a critical global development gap, risk-reward balances still need to be more easily agreed before a self-perpetuating success story is likely to take flight. If this understanding influences new generations of stakeholders, the arrival of a concrete movement may finally dispel any lingering wariness from the current wave of boom-time sloganeering.

"Following the announcement of One Belt One Road initiative, there has been a combination of experienced players and less experienced newcomers – and it's not difficult to tell which ones are which," says CITIC's Wang. "Experience is really the differentiator here, but that's fine because they will learn and the market will grow."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.