China's sharing economy: The peer effect

Bicycle-sharing is following the lead of ride-hailing in China – with start-ups consuming large amounts of capital in a battle for market share. What does it say about the broader sharing economy opportunity?

Ofo launched on the campus of Peking University in 2015 as part of a student bike-sharing project. Six co-founders pooling their savings and borrowed cash wherever they could to provide the RMB150,000 ($21,800) required to get the business off the ground.

After five funding rounds over the course of two years, Ofo is now worth in excess of $2 billion. Its backers include DST Global, Coatue Management, local ride-hailing platform Didi Chuxing and Alibaba Group's financial affiliate Ant Financial. The company also claims to be the world's largest bicycle-sharing platform. Over three million of its yellow bikes can be found in more than 50 Chinese cities, and they have also hit the streets of London and Singapore.

Wei Dai, a 26-year-old co-founder of Ofo, says this capacity for expansion is largely the result of the inefficiency of existing programs: Users can only pick up the bikes at specific locations so adoption rates are low. "The explosive growth of bike-sharing in China is because of business model innovation – users can pick up and park bikes anywhere at any time. It's much more convenient and also very profitable. In some Chinese cities, we are already recording net profit margins of 40%," he explains.

Ofo's rise is also a testament to the bike-sharing battle that has broken out in China's cities over the past 18 months. Major urban centers like Shanghai and Beijing are now filled with at least 20 different colors of bike, each one representing a different company. Mobike, which paints its machines in striking orange, is Ofo's closest rival. The company has 3.65 million bicycles in 50 cities, and has completed four funding rounds as well as receiving several strategic investments.

While the flood of private capital into ride-hailing platforms – the first sharing economy segment to gain traction in China – was rapid, bike-sharing services have upped the pace even more. Investors looking at start-ups targeting co-working spaces, power bank rental and luxury clothing sharing are entitled to ask whether the competitive frenzy that has gripped existing segments of the sharing economy will be replicated elsewhere. It also remains to be seen when this excitement translates into actual returns.

Demand and supply

The sharing economy is not a new concept. From offering a colleague a lift to work to putting up a friend in a spare room, the sharing of resources is a longstanding part of social engagement. What has changed in recent years is the emergence of technology platforms that allow individuals and organizations to monetize their underutilized assets by sharing them with strangers for a fee.

A number of terms – collaborative economy, on-demand economy, and rental economy – have entered technology parlance under the sharing economy umbrella, and Uber and Airbnb are perhaps best global examples of start-ups that have flourished by connecting unused supply with unmet demand. However, the scope of this universe extends well beyond transportation and accommodation, taking in skills, knowledge and money as well.

"A wide range of assets are sitting in the market that are not utilized," says Jixun Foo, a managing partner at GGV Capital. "What the internet does is compress the whole value chain, allowing users to find the things, such as content like video and pictures, as well as physical items such as bikes and luxury clothes, to which they want to access in a ready manner. The reduction of friction in these transactions accelerates the whole concept of sharing economy."

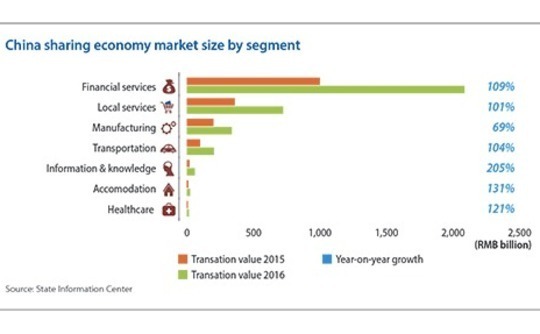

Attempting to capture the value of the concept in China, a report released by the government-backed State Information Center considered activity ranging from the sharing of holiday accommodation to office space, and from manufacturing to the service sector. It concluded that transaction value came to RMB3.45 trillion in 2016, up 103% on the previous year. The sharing economy is projected to see average annual growth of 40% over the next few years and account for more than 10% of the GDP by 2020. By then, 5-10 mega-enterprises are expected to straddle the space.

One key characteristic of these start-ups is they address an imbalance between demand and supply in parts of the traditional Chinese economy where there is high transaction frequency. Whether a platform is processing taxi rides, meal deliveries or

manicure services, there should be enough people placing enough orders for the commissions to justify fulfilling some kind of intermediary function.

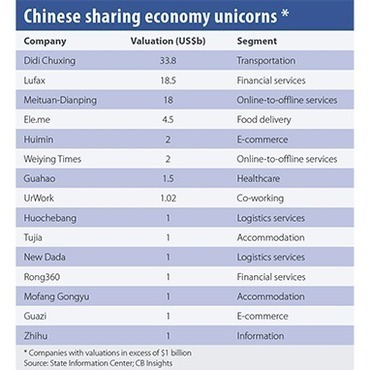

Tencent Holdings backed several companies in the first wave of sharing economy start-ups in transportation, food delivery and local services – it is a shareholder in Didi, Meituan-Dianping and Ele.me – and has invested in Mobike as part of the second wave. Jeffrey Li, a managing partner at Tencent Investment, identifies two main differences between the two sets of companies. While the likes of Didi and Meituan-Dianping basically collect information and connect suppliers to prospective customers, the next generation are primarily asset owners.

In short, Didi does not own the taxis it routes to consumers who want to travel from A to B, the cars belong to the drivers personally or to third-party fleet operators. Ofo does own its bicycle fleet and rents machines directly to consumers. It is a very different business model in terms of the capital it requires and the challenges it presents.

"Bike-sharing is not shared economy, it's fundamentally an asset leasing business and we only have to look and see if it's making money," says Jingyang Wu, a managing director at CITIC Private Equity, a backer of Didi, Ele.me and Ofo. "The company [Ofo] can control the cost of running those assets – in this case, bicycles – and generate revenue from customer usage. If you can reach the right usage per bike, you will make money. But this depends on a set of assumptions that need to be rigorously studied and tested – the lifespan of a bike, usage frequency per bike, manufacturing and maintenance costs."

Capital concerns

Didi has consumed huge amounts of capital, not least before its merger with Kuaidi Dache when the two companies were battling for market share. The bicycle-sharing start-ups appear to be following a similar path, and perhaps the even shorter gaps in between their fundraising rounds can be explained by the need to invest upfront in vehicle inventory. Beyond that, however, capital goes towards subsidies intended to induce customers to use their service above the others.

With businesses of this nature, VC investors must identify companies with addressable markets that could be worth tens of billions of dollars and then bring in late-stage players to sustain momentum. If they don't move early enough, it is very hard to catch up unless a company has an innovation strong enough to upset the established order. This explains why bike-sharing start-ups such as Bluegogo and Hellobike raised Series A and B rounds but have since floundered.

"The barrier to entry exists when a player becomes the dominant player in a city and users frequently use that app on their mobile phone. Capital has become an important factor to allow top players to reach critical mass quicker than their competitors," adds Wu of CITIC PE.

Once critical mass is achieved, the hope is that these companies will turn profitable, having switched focus from subsidy-driven efforts to win market share to longer term business development. The evolutionary curve may even be shorter for the second wave of sharing economy start-ups. "For the bike-sharing business – Ofo charges RMB1 per ride – the cost for acquiring customers is lower than for the likes of Ele.me, Meituan-Dianping and Didi," says Kelly Poon, Greater China partner at Atomico.

"It will take some time for some previous high-profile companies – which have raised a lot of funding from investors – to justify these substantial financial outlays and show that they can support large IPOs, as the public market is still cautious about the private technology companies. Those players also have to show that they are clear leaders in their verticals," says GGV's Foo.

The strategy, therefore, appears to be more of the same: these companies have to become more dominant, achieve even greater scale, and then push for an IPO. While the likes of Ele.me and Didi are focused on doing this in their core businesses, Meituan-Dianping is trying to expand into other sharing economy verticals. It launched ride-hailing service in Nanjing to compete with Didi and then entered the short-term vacation rental space in which Tujia is the major player.

"The scale of the platform is critical to do all kinds of local lifestyle services. With 240 million annual active users, we are the second largest e-commerce platform selling products and services after Alibaba. This mega platform enables us to better connect merchants with consumers, and it is also an important reason why we are able to enter new verticals. We might be a late-mover into a vertical but we have the resource to catch up," says Shaohui Chen, senior vice president at Meituan-Dianping.

Rather than go head-to-head with established players in ride-hailing and vacation rental, Meituan-Dianping wants to convert existing customers of its on-demand delivery and restaurant-booking services. This lower cost approach to customer acquisition was previously employed to expand into hotel reservations and food-delivery services, which already had dominant players when Meituan-Dianping came in.

The company will stick to its platform strategy – there are no plans to adopt an asset-leasing model – and work with the service providers. This includes making its technology, data and customers to these providers, essentially making it easier for them to do business through the Meituan-Dianping platform than with single vertical players because there are more cross-selling opportunities. "That's the power of sharing economy – enabling service providers to operate more efficiently," Chen adds.

Meanwhile, the new generation asset-heavy businesses are looking for scale overseas. Several bike-sharing companies – Mobike, Ofo and Bluegogo among them – want to enter markets where feel their business model is superior to those of domestic players. For example, Ofo has a year-end target of expansion into 20 countries, including Japan, France, Spain, Germany and the Philippines. However, the long-term plan is to become an asset-light platform business.

"Our ultimate goal is to build a platform through which all third-party bike-sharing companies can rent their bikes," Ofo's Dai says. "We couldn't do this at the beginning because there weren't many companies operating under the same model as us, so we had to provide our own bikes. Now, it's clear there are two main players in the market, and others don't have frequent usage-per-user. We can provide a solution to them by plugging their services into our platform."

Last blast

In this sense, pursuing an asset-leasing strategy is a means to an end; or a means to create a sharing economy opportunity where there is unmet demand but not a flexible source of supply. Similar approaches are evident in other areas. About 15 power bank rental start-ups – charging stations for smart phones and other devices in public places such as restaurants, KTVs and subways – have attracted VC funding. In recent weeks, Tencent and Vision Plus Capital have led a Series A round for Xiaodian, while Energy Moster was backed by Shunwei Capital Partners, Hillhouse Capital and Xiaomi.

There has also been significant activity in the co-working space market, which in its purest form involves a property owner dividing up office space into small pieces and renting it to start-ups, and in online clothes rental, where users hire luxury clothes on a temporary basis.

"Within the sharing economy, we like the rental idea because its business model is clear – you buy something and then rent it out. What you need to do is to find a market that's big enough," says Xiang Gao, a founding partner at Banyan Capital. "The real C2C sharing model is difficult to scale up in China, in my view. First, managing a variety of unstandardized assets owned different individuals is difficult. Second, it's hard to know whether there is a sustainable model at the beginning because a platform only gets fees from facilitating transactions between two parties."

Clearly, sharing economy represents an investable concept in a limited number of areas, and each one has its own nuances. For example, clothes-sharing is unlikely to generate the same frequency of usage per unit as bike-sharing for hygiene reasons: users have no problem riding a bike that has been ridden by 15 others, but they might not apply the same rule to clothes. Power bank rental is seen as having the potential for scale, but it remains to be seen if the demand is there.

Indeed, it is hard to list services beyond transportation, food delivery and local services that pass the transaction frequency test – at least in the current internet-enabled retail environment. Bicycle-sharing may therefore represent the last large-scale vertical in China's sharing economy, offering a final glimpse of the ferocious competition and capital-raising that has characterized the emergence of the sector.

"In the next 3-5 years, it is unlikely that there will be any large opportunity in the on-demand services or the sharing economy," says Wu of CITIC PE. "It will be difficult for new companies to reach the scale of Didi, Ele.me or Ofo. All the high frequency and wide coverage verticals have been taken by major players. Opportunities will only come when new technology allows new business models to take over existing ones."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.