China NPLs: Great expectations

Foreign private equity firms are positioning themselves to address an anticipated surge in non-performing loan sales to third-party investors. Will the reality match the hype?

"I previously did NPLs [non-performing loans] in Japan and Korea during the Asian financial crisis. In the 20 years since then I've been following the China market and thinking about whether this was a scalable opportunity, and every time the answer was no," says Kei Chua, a managing director with Bain Capital Credit (BCC). "But this time it's different."

BCC is a seasoned distressed debt investor globally but it has previously barely touched NPLs in China. Now, though, with the firm looking to raise up to $1 billion for its first Asia special situations fund, NPLs are expected to account for as much as half of the overall China activity. BCC has 14 people in Asia dedicated to special situations – other professionals in the firm provide support – and there are a dozen more in China through arrangements with asset servicers.

The firm is not alone in wanting to deepen its talent pool. Lone Star, Oaktree Capital Management, Avenue Capital Group, PAG and Goldman Sachs are among those looking at distressed debt with renewed interest. One industry participant – echoing sentiments expressed by several others – says there has been "an open hit out on anybody who has worked at Shoreline Capital," perhaps the most established China NPL investor.

Two years ago, as it became apparent that casualties from the 2008 credit boom China instigated to minimize the local effects of the global financial crisis were filtering through the system, there was a lot of talk from foreign investors but little action. The recent recruitment drive suggests investors are gearing up for a concerted push into the market.

Then and now

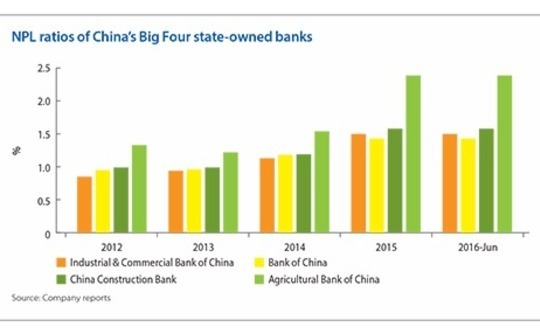

China's loan book has quadrupled in size since the mid-2000s when investors last piled into the space only to find that deal flow was not as rich as expected. Assuming the banking industry's NPL ratio is five times the official estimate of around 1.7%, what Chua currently sees as a $200 billion opportunity could reach $1 trillion (other estimates are as much as $3 trillion, based on a higher perceived NPL ratio). But much rests on the government making banks take action and investors having the right people and processes in place to generate meaningful returns.

"It's not like the first cycle in 2001-2007 when there was an orchestrated process by the government to sell off the NPLs," says Ted Osborn, a partner at PwC who focuses on restructuring and NPLs. "This time around there is a lot of musical chairs – banks selling at face value to related companies, talking up securitizations and debt-for-equity swaps – and the problem isn't being dealt with. Foreign investors will be able to find opportunities if they are persistent, but as to when the market is going to get really big, I don't see a catalyst for that right now."

Second, the enforcement infrastructure is much improved. Courts have become increasingly efficient in resolving NPL cases, making it easier for investors to predict cash flows. There is also more information to work with thanks to closer scrutiny by the banking regulator and greater transparency in the property market regarding land title ownership and registration of collateral.

"You didn't really have an active market for selling collateral until the last few years," says BCC's Chua. "There are tools that enable you to triage portfolios from your desktop before engaging in deep underwriting. You have good information on buyers, comparable transactions you can look at in order to price effectively, and outlets for marketing properties that are for sale."

Third, the Big Four asset management corporations (AMCs) established with the sole purpose of resolving the major state-owned banks' NPLs in the previous cycle have diversified their business lines considerably. The bulk of their income comes from other forms of financing – from direct lending to buying real estate projects to private equity – which means they are incentivized to sell on NPL portfolios as quickly as possible to third parties rather than try to resolve them.

On top of that, the sheer volume of NPLs coming through the system is more than the Big Four can handle, hence the decision to alleviate the bottleneck by awarding licenses to more than 20 new provincial-level AMCs. These groups are looking to build up resolution capabilities and Ben Fanger, who departed Shoreline last year to establish ShoreVest Capital Partners, claims to have been approached by several of these groups with a view to forming partnerships.

Taking aim

ShoreVest is tracking $20 billion worth of potential investments and is primed to make acquisitions using capital sourced from a global asset manager. Deals can be as small as $10 million in size and as large as $300 million, with an average of $30-50 million. BCC is seeing opportunities in a similar range: RMB200-300 million ($30-44 million) investments in portfolios with original principal balances (OPB) of anything from RMB600 million to RMB2.5 billion.

PAG bought its first portfolio last year, which had an OPB of RMB10 billion. It was an auction process run by an AMC, as required by the regulator, but essentially a bilateral deal negotiated with a bank; the AMC received an intermediary fee. In these situations, the buyer approaches the bank early on and might get two months to conduct due diligence. The portfolio is then opened up for general bidding, but with a one-week turnaround – generally insufficient time for rival bidders to firm up the pricing.

"It wasn't long before we started receiving calls from local guys who wanted to buy some of the loans," says Eddie Hui, a managing partner in PAG's absolute returns division. "You never know why they are interested. We did our own due diligence, but the one thing they can usually quantify is the personal guarantee: they might be able to leverage their local knowledge to collect money from borrowers in situations where the collateral value doesn't look good."

In a portfolio of this size comprising approximately 40 borrowers – and more than one loan per borrower – packaging up portions for sale to third parties is not unusual. For example, an investor might identify 50 loans in a portfolio of 200 where the seller hasn't priced in full value and by resolving those situations alone it can more than cover the reserve price. Those NPLs warrant active management, but the rest do not, so they are offloaded to other investors who think they can extract value.

The question for foreign investors targeting the NPL space is the extent to which these local players are emerging as genuine competitors as opposed to just downstream buyers. While renminbi-denominated investors tend to occupy the sub-RMB200 million space, which means there is minimal overlap with their offshore peers, there are reports of domestic firms with resources to address RMB500 million transactions. AMCs are also tailoring transactions to suit the smaller end of the market.

"The AMCs want to deal with local people because there are fewer approvals and less scrutiny of the transactions than if they were to sell to a foreigner," says PwC's Osborn. "We lined up a deal for a foreign investor but the AMC got tired waiting for a decision and said, ‘If you don't get back to us by this date we're going to sell locally because these guys are ready to go.' We didn't get back to them in time and so they sold to a local guy. It was a $30 million deal, sizeable for a local player, so it was broken up into pieces. While a $100 million deal would be unusual, the numbers are creeping up."

Domestic rivals

Local capital has poured into the space over the last 18 months, much of it from traditional private equity firms and vehicles backed by listed companies. Pricing has adjusted accordingly. "The prices in recent transactions have been pushed to levels that are difficult to justify from Shoreline's perspective. In our view, the market will cool down because it is important to have the right disposition capabilities and capital structure," says Xiaolin Zhang, co-founder and managing partner at Shoreline.

According to multiple industry participants, the structures are often far from healthy. A lot of the capital ultimately comes from HNWIs who participate in expectation of a 2-3 year holding period, far shorter than traditional NPL funds. Structures are also highly levered, with a senior debt tranche provided by banks at high cost or through products sold to retail investors – in some cases online peer-to-peer lending networks have been used – on the understanding of a guaranteed return.

"If it is two-year money targeted at a couple of portfolios, they then need to be resolved, pay cash interest and pay capital to investors. The return is the spread between that high net worth money and what you think you can resolve on the loans – and when bidding so high for small portfolios there is a real risk of not achieving those returns," says BCC's Chua. "The whole concept behind a portfolio is the diversification it provides and the ability to scale up. I'm not sure what the smaller guys are doing is sustainable."

Scale is something local players understandably struggle to achieve. Their value proposition is based on detailed knowledge of a handful of borrowers and relationships with regulators and legal officials within specific geographic areas. Executing the same strategy with several hundred borrowers on a nationwide basis is a substantial undertaking.

Shoreline, for example, has a team of more than 40 people in China and claims to have signed agreements with over 50 servicers across the country over the last few months. In addition, the firm is considering opening offices in different provinces that would serve as points of contact for servicers and outposts for gathering information on what local banks and AMCs have in the pipeline. "The NPL business is a very local business, and first-hand information from the market will help us to better serve the clients – banks and AMCs – as well as our servicers" says Tony Liu, COO at Shoreline.

In this context, scale is also a concern for any foreign investor addressing the China market. More advanced industry infrastructure means foreign distress specialists can introduce global best practices and technology, allowing them to track portfolios more systematically, but they still need bodies on the ground to service and enforce on loans.

Local servicing platform Gao Fei employs about 50 people and is increasing headcount by nearly 10% a month as it takes on more jobs from domestic and offshore groups. Phil Groves, founder and president of DAC Management, Gao Fei's parent, observes that there is "a lot of fear" among foreign investors about going into China without the a partner that has the full set of licenses. But should an investor maintain a skeleton staff in Hong Kong and rely on outsourcing or build up an in-house team?

Hui describes PAG's model as a combination of the two. The firm currently has six people dedicated to China NPLs, four of whom are in Shanghai working on the portfolio acquired last year. The plan is to increase headcount with each additional purchase. "Maybe there will be 10-15 when we reach a meaningful size," Hui says. "We will still use servicers. We are more hands-on than some people, but we can't do anything like the US and Europe, building a 100-person servicing team."

Not all investors consider the investment to be worth it. Edwin Wong took part in the first China NPL transaction to feature foreign investors in 2002 while at Lehman Brothers. SSG Capital Partners, a spin-out from Lehman's Asia special situations business, has "strategic plans" for the space, but it does not believe the returns are at present commensurate with what its LPs expect. Wong cites local competition and a shortage of sizeable portfolios as the primary obstacles.

These conditions can leave investors in a bind: it is unclear how big the China NPL opportunity will be in this cycle or how long it will last, but if they do not properly engage at the local level they will be left scratching the surface. While the improvements in loan quality and the enforcement regime are helpful, they are also a leveler. A portfolio of 10 loans pledged by real estate assets in Shanghai will be heavily contested by investors, pushing the pricing up and the profit margin down.

Complexity counts

ShoreVest's Fanger prefers portfolios that comprise more than 30 loans, so there is a greater scope to take advantage of information asymmetries. He compares the current scenario to the previous cycle, when a number of global investors arrived with mandates to acquire concentrated, highly secured portfolios. They ended up paying $0.30-0.40 on the dollar, leaving little margin for error if it turned out that a few assets were not as secured as previously thought. Around the same time, Shoreline faced zero competition in buying a portfolio of more than 1,000 loans for $0.02 on the dollar.

"Many investors assumed that anything under $0.05 was garbage. There's a fundamental flaw in thinking that a portfolio with fewer loans that are senior secured has to be a lot safer than one that's harder to understand, has more loans, and some of them have problems," Fanger says. "This business requires a commitment to building a local platform and having decision makers who can communicate in a seller's native language in order to create relationships for sourcing and managing deals."

Should more substantive deal flow emerge, more foreign investors might be willing to make this commitment – although it follows that local competition would intensify as well, ultimately to the point where there is more institutional participation. As it stands, though, initiatives such as NPL securitization are seen as symptomatic of a tendency to play for time: securitization removes NPLs from a bank's balance sheet but they are still under its management and they still have to be resolved at some point.

PAG's Hui sees commercial real estate as a helpful proxy for the broader distressed investment opportunity. Yields are lower than the interest developers are paying on their bank loans, but as long as asset prices keep rising, the market is unconcerned. The question then becomes: How low would yields have to fall before banks recognize the loans as non-performing and start to foreclose?

"Eventually, they will have to deal with this problem," Hui says. "If the government admits it has a 10% NPL ratio and wants to clean everything up in three years, we would have three years of great deal flow and not much after that. If they say the ratio is 2% and will stay that way for 10 years, it's a softer landing, but on one hand they are selling NPLs and on the other they are creating more every year. We don't know how aggressive the government is willing to be on this."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.