China VC spin-outs: Daddy issues

Several managers in the latest generation of China VC spin-outs retain close ties to their former corporate parents. These relationships can deliver great deal flow, but also governance headaches

Spin-out number one: Genesis Capital. After spending seven years as head of M&A at Tencent Holdings, Richard Peng launched his own firm in 2015. Genesis focuses on growth stage investments, leveraging its networks and expertise with a view to helping Chinese internet start-ups achieve critical mass. Peng is said to be on course to beat the $400 million target for his debut fund, having decided against raising capital from his former parent in order to attract institutional LPs.

Spin-out number two: a consumer fund launched by online-to-offline (O2O) services platform Meituan-Dianping. While professionals have been hired to oversee investments, they are subordinate to the parent's corporate development unit – and the primary objective is to expand its ecosystem through consumer sector deals. The fund, which is targeting $440 million, has received commitments from the likes of Tencent and New Hope Group, but Meituan-Dianping is the anchor LP.

If Genesis is truly independent and the Meituan-Dianping vehicle isn't even independent in name, then GenBridge Capital sits somewhere in the middle. Two of its three founders worked in M&A at online retailer JD.com, but the GP is wholly-owned by the team, the investment committee is independent, and GIC Private is anchoring the debut fund of up to $500 million. However, JD.com will contribute capital, people and deal-sourcing capabilities to the fund, and take half of the carried interest.

These three spin-outs offer a snapshot of how a new generation of venture capital firms in China is emerging. Over the past two years, various teams and individuals have struck out on their own, leaving established VCs or domestic internet giants such as Baidu, Alibaba Group, Tencent and JD.com. But in a competitive investment environment – yet one in which it is increasingly difficult to raise capital – how do these new arrivals convince international LPs that they are worth backing? For those with a corporate heritage, the answer might be not stray too far from their former parents.

"We are open to these corporate-backed venture funds because we do feel that China is a competitive market. If you have some kind of strategic backing and you manage it well, it's a very powerful weapon. But it's a double-edged sword. You have to get the balance just right because in the US dollar world, investors are more cautious about conflicts of interest," says Doris Guo, a partner at Adams Street Partners.

VC 3.0

According to Tommy Yip, founder of fund-of-funds Unicorn Capital, which specializes in backing emerging Chinese VC managers, China entered the VC 3.0 phase in 2013. This was when younger professionals increasingly started spinning out from top firms in order to address different kinds of market opportunities. It is distinct from VC 2.0, when GPs would leverage whatever affiliations they could to get started, whether it was a US VC firm or a Chinese corporation like Legend Holdings.

Shunwei Capital Partners and Yunfeng Capital, both founded in 2011, were arguably the progenitors of this trend. The former was set up by Lei Jun, a serial entrepreneur and angel investor best known for smart phone maker Xiaomi; the latter is the brainchild of Jack Ma and David Yu, founders of Alibaba and Target Media, respectively, who put assembled a roster of Chinese entrepreneurs as founding partners and Fund I LPs, with a view to leveraging their networks and operational capabilities.

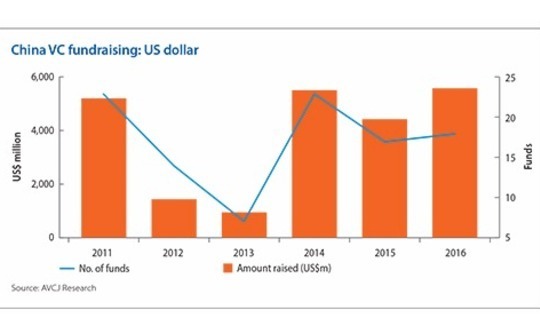

A total of $5.5 billion was committed to US dollar-denominated China VC funds in 2014, more than for the previous two years combined. Most of the money went to established names, but there were a couple of fully-fledged spin-outs: Banyan Capital was established by a team from IDG and Source Code was founded by a former executive at Sequoia Capital China.

The fervor surrounding Alibaba's IPO in late 2014 translated into growing appetite for China VC exposure across the spectrum. More spin-outs followed: Volcanics Venture from IDG, Yunqi Venture from Sequoia, and Blue Lake Ventures and Joy Capital from Legend Capital. Early-stage investment was a common theme.

"Senior professionals are seeing new opportunities in the market and they are confident enough to launch their own firms. Sometimes it is because their existing organizations are getting larger and investment strategies are changing. For example, the focus may shift from growth capital investments to larger deals – and because these professionals want to continue doing what they have done before, they decide to leave," says Mingchen Xia, a managing director at Hamilton Lane.

Fundraising for US dollar China VC vehicles hit a new high of $5.6 billion in 2016, as LPs dialed up their exposure to technology, media and telecom (TMT), healthcare and other bastions of the new economy. A growing number of spin-outs from corporates are looking to win their backing.

Ameba Capital, launched for ex-Alibaba executive Andrew Teoh, has scaled up in fund size, Baidu M&A head Hesong Tang established Xianghe Capital, and Peng went to market with Genesis. Other senior alumni of Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent have forged ahead in the angel space, with the likes of Unity Ventures and Crystal Stream Capital.

Close relations

The sweet spot for corporate spin-outs is growth- to late-stage investments, given where they tend to have focused in their previous organizations. However, this notion of "more of the same" doesn't resonate with all LPs. When assessing the track record of someone who has come out of a corporate, it is important to note that investments could have been motivated by strategic considerations rather than pure economic rationale. Moreover, it is often had to tell whether successful deals were driven by the person or the platform.

"When professionals from large TMT companies approach us regarding their new funds, the first question I will ask is: ‘Has your strategy changed?'" says Jun Qian, head of China at Swiss asset manager Adveq. "In the past, they might have invested in every single part of the sector in which the corporate operates. If they tell us they backed 300 companies in the space of two years, that's probably not the kind of investment style we like."

On the other hand, a corporate background and relevant connections can translate into deeper industry insights and better deal flow. Vision Plus Capital, set up by Alibaba co-founder Eddie Wu and James Wang, formerly a principal at Qiming, is a classic example. Based in Hangzhou, not far from the Alibaba headquarters, the GP positions itself as a market-oriented VC that leverages the Alibaba's ecosystem. Having established through research that start-ups are more likely to be successful if they have ex-Alibaba employees on their founding teams, Vision Plus favors with this profile.

"When start-ups raise Series C or D rounds of approximately $1 billion, they look for Alibaba or Tencent as their strategic investors, whether it's because they want to leverage Alipay's user base or launch a product in partnership with WeChat. We want to invest in those start-ups early on," says Wang. "By being close to Alibaba's headquarters, we quickly find out which employees have left to start their own businesses, and we make a reference call with their respective senior managers and understand more about their personalities and strengths."

Although a close relationship with Alibaba is part of the Vision Plus DNA, Wu and Wang do not want to be beholden to the e-commerce giant. As such, they are open to collaboration with groups such as JD.com and Tencent and half of the firm's investment team previously worked at Temasek Holdings and GGV Capital. According LP sources, Alibaba doesn't hold a stake in the GP, but the company and several of its executives have contributed capital to the fund.

From the perspective of an offshore LP, the presence or absence of these fund commitments are indicators of how close a spin-out GP remains to its former parent. Xianghe counts New Enterprise Associates (NEA) as a significant LP, but the family office of Baidu founder Robin Li is also said to be an investor. The implication is that Tang remains plugged into the Baidu network.

Other arrangements are more formal. When Alibaba invested $100 million to Yunfeng's second fund, the company justified the move in its IPO prospectus by saying the LP tie-up "formalized an institutional relationship" with the GP. The GenBridge-JD.com relationship appears to be forged along similar lines. In addition to the corporate participating in the fund and enjoying a piece of the carried interest, JD.com founder Richard Liu and other management team members will make LP commitments.

If the alliance is too close, however, LPs can get uncomfortable. "Some captive funds handle conflicts of interest very well through a standardized governance structure. They ensure investment decisions are made independently and the team is incentivized by the carry. We prefer the investment team to keep a majority of the carry. If the parent takes a large portion, the team might separate because they are not fully incentivized," says Hamilton Lane's Xia.

Independence day?

For fully captive VC firms, there is also the longer-term question of whether they want to become independent. It is estimated that about 100 funds were launched in 2014 by A-share companies and private enterprises. These could feasibly become the next generation of spin-outs seeking capital from international LPs, but it remains to be seen on what terms this might happen. How will ownership of the GP be structured and the economic interests divided up?

Lilly Asia Ventures (LAV) represents an example of a successful transition to independence, while retaining elements of an alliance with the former parent. Between 2008 and 2010 it was a corporate VC arm under Eli Lilly, and the global pharmaceutical player served as the sole LP in the first two funds raised following the spin-out. From Fund III onwards, LAV has raised capital from a mixture of sovereign wealth funds, fund-of-funds and family offices, while Eli Lily's contribution has gradually reduced.

Parallels can also be drawn with the financial world and the relationship between global VC firms and their China affiliates. The China team of Lightspeed Partners went independent in 2012 and received a substantial LP commitment from the parent for its debut fund. More recently, Long Hill Capital and Redpoint China came to similar arrangements with NEA and Redpoint Ventures, respectively.

Spin-outs are likely to continue as China's venture capital market matures, but it remains to be seen how easily these managers can raise money. Many North American LPs are no longer expanding their portfolios by number of China GP relationships, so a new arrival would have to make a strong case for displacing an incumbent, underpinned by a solid track record. Prospective investee companies would expect to hear an equally convincing argument before taking money from these managers.

"Earlier spin-outs came from a variety of different firms, but now new franchises have to make more successful investments before they are attractive to LPs and entrepreneurs," says Adams Street's Guo. "It is difficult for new firms to establish themselves."

The pressure doesn't necessarily abate once a spin-out raises its first fund. When the GP returns to market, LPs want to see evidence of the investment thesis working in practice and of steps being taken to reach the next level. Banyan started with three founders from IDG but in the space of three years it has evolved into a team of 30 with financial and operational backgrounds.

"It is challenging to build and develop a new firm from the ground up. Everyone questions whether you can still do well on leaving your old firm, and whether you can attract new talent, cultivate a sustainable corporate culture, and develop a differentiated investment strategy," says Zhen Zhang, co-founder of Banyan. "But when a firm grows to a certain size, the background of the founding partners becomes less important. You then face questions about improving internal systems and strengthening team work."

SIDEBAR: Private equity spin-outs

he first private equity spin-out in China happened when the industry itself was barely five years old. In 2002, brokerages were barred from owning captive PE units, so a team from China International Capital Corp. (CICC) departed to form CDH Investments. They started out with four LPs and $100 million in capital.

Other spin-outs have followed at irregular intervals. FountainVest Partners was created in 2007 by a team out of Temasek Holdings, while Fred Hu, formerly Greater China chairman at Goldman Sachs, founded Primavera Capital in 2010. Other firms, such as Boyu Capital, represent amalgamations of executives from several firms. More recently, Forebright Capital and Everbright Reinfore have both come out of China Everbright International. Activity has inevitably been more frenetic among the renminbi-denominated managers.

"Spin-outs happen in China all the time. It's a natural evolution when a market grows and becomes mature. Before 2011, there were managers who spun out from the state-owned enterprises and banks and launched first-time PE funds," says Jun Qian, head of China at global asset manager Adveq. "Between 2014 and 2016, many VC professionals spun out from big names and that caught people's attention."

The headline spin-out for 2017 involves David Liu and Julian Wolhardt, who previously led KKR's private equity business in China. The pair have yet to launch a fund or outline a strategy, but it is suggested in some quarters that they might start by raising renminbi capital for deployment on a deal-by-deal basis so as to avoid conflicts with KKR. Ultimately they must convince LPs that they can be as effective outside a big organization as they have been inside one.

"When managers spin out, especially from brand-name platforms, LPs will ask: Are you able to effectively source deals and add value to the portfolio companies when you're not holding the same business card? How much did the brand contribute to your previous success?" says Chris Lerner, partner and head of Asia at placement agent Eaton Partners.

LPs must provide their own answers to these questions through comprehensive due diligence. In emerging markets like China, global private equity firms enjoy little or no name recognition so they rely heavily on local teams to build out their brands among the founders and owners of local businesses. As a result, the personal touch counts for a lot.

"At the end of the day, private equity is a people business. For a buyout of a family-owned business that is not intermediated, sourcing and execution is often the responsibility of individual managers. If one of these individuals leaves a firm, track records can be verified by speaking to the portfolio company management and to banks that provided financing to the deal," says Niklas Amundsson, managing director at Monument Group.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.