India: Draining the PIPEs

PIPE deals remain a significant part of private equity in India, but a slowdown in recent years has prompted investors to evaluate strategies and the place for public market deals in private portfolios

Indian engineering firm Dynamatic Technologies was relatively unknown in the country's private equity community in 2010 – and that was just the way Samena Capital wanted it. The firm was on the lookout for local businesses that were overlooked by the wider investment community, and Dynamatic hit the sweet spot: it was listed, so most PE investors avoided it, but at the same time its liquidity was too low for public market investors to take much interest.

Samena feels Dynamatic has more than justified its initial $8 million investment. From INR944.80 at the time of the original deal, the company's share price has more than tripled – most recently closing at INR2,890. It was even higher at the time the GP exited the stake held by its first find in October 2016, earning a return of more than 2x (the firm retains an 8.8% stake acquired through its second fund).

"We identified this company five or six years ago when it did $1 million of sales to AirBus for a component. Today it's the hottest ‘made in India' story. And we've seen that evolution happen over the last six years," says Chetan Gupta, senior vice president at Samena. The firm sees Dynamatic as powerful evidence for why Indian PE investors should not overlook PIPE deals, demonstrating the kind of rewards available to managers who do their homework well.

The argument is well known among India-focused GPs and many find it persuasive. However, there are obstacles to pursuing PIPEs in India, among them a decline in opportunities and growing skepticism from LPs. Investors that want to look for treasure buried in India's public markets must form a convincing strategy and be prepared to justify their approach to those who hold the purse strings.

The pipeline

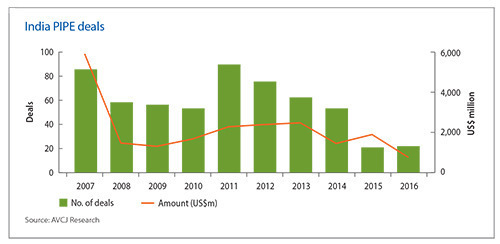

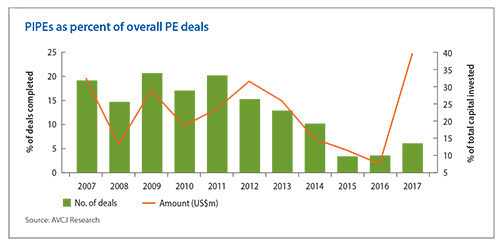

PIPE deals have historically accounted for a significant proportion of private equity transactions in India. AVCJ Research shows their share of overall PE investments was above 10% in each year since 2007 until 2014, while their share of the amount invested in dollar terms only dropped below 10% in 2016 – and so far this year the latter number has risen back to just below 40%.

By contrast, over the same period China has never seen PIPEs represent more than 10% of overall deal flow. The PIPE share of dollars invested in China has consistently been higher than in India – but this figure is inflated by deals such as Singapore state-backed investment vehicle Temasek Holdings' multiple investments in Chinese state-owned banks of $1 billion or more.

While the strong presence of PIPEs in India's PE market is undeniable, they have shown a steady decline in recent years, going from a peak of 89 deals in 2011 to just 22 deals last year, a drop of more than 75%. Their share of overall deals also dropped from 20% in 2011 to just 3.6% in 2016.

This development has generated little concern and some relief in the investment community, with LPs in particular welcoming it as a sign of growing maturity among India-focused GPs.

LPs' hesitance to back GPs that pursue PIPE deals stems from multiple sources. In the case of UK-based development finance institution (DFI) CDC Group, the companies that GPs are most likely to find in the public market are correspondingly least likely to meet the social development goals that are most important to the institution. "Investing in a listed company, which is hopefully already able to mobilize commercial capital from the market at much cheaper rates, is not a good destination for our capital," says Alagappan Murugappan, managing director of Asia funds at CDC.

Murugappan takes a similarly skeptical view of the financial. Unlike CDC's social goals, this perspective is shared by many of the DFI's fellow LPs, which in recent years had begun to wonder, increasingly vocally, why they should pay the customary overhead for GPs to make passive investments in public companies. This investor dissatisfaction, upon being noticed by PE managers, had the desired effect.

"GPs were being told by LPs that if they wanted to do a PIPE deal, they weren't going to get the same amount in terms fees [2% management fee and 20% carried interest], because then the LPs would much rather go to a public fund manager than a private equity fund," explains Vikram Hosangady, head of India private equity at KPMG. As a result, he says, "private equity funds have become fairly averse to doing PIPE deals unless they have to."

General Atlantic's investment in PNB Housing Finance represents one recent case where circumstances seemed to dictate a PIPE transaction: the GP joined the mortgage lender's IPO last year as an anchor investor and later bought an additional INR5 billion worth of shares after its debut. It was a way for General Atlantic to gain exposure to an exciting company and segment without trying to outbid other private investors.

This is the type of PIPE investment that usually comes to mind among PE professionals, and is the chief driver of criticism both from LPs and from other private equity firms that see this approach as lazy and dangerous: the former because it requires none of the real work or talent that should go into setting up a private investment; the latter because it tends to lead to funds clustering into a few popular sectors without sufficient diversification and thus protection for their investors.

Loving the unloved

By contrast, proper PIPE investing means going in the opposite direction: looking for companies that have been largely ignored by both public and private investors despite the increased visibility of being listed, and that can benefit from the guidance that an experienced PE investor can bring to bear.

India's market offers some unique attractions in this regard, largely owing to the changing nature of its public markets and its evolving regulatory environment. Notably, a widely held perception among PE professionals is that many of the closely-held companies on India's public bourses should not be listed at all, since their characteristics align more with those of private companies.

These include companies such as the earlier mentioned Dynamatic, as well as commercial vehicle and motorcycle manufacturer Eicher Motors, another former portfolio company of Samena. Gaurav Ahuja, managing director of ChrysCapital, explains that many older Indian companies went public too early in their lifecycles due to difficulties private companies face in securing financing for expansion. Since their listings, in some cases decades ago, these businesses have continued to attract little attention, resulting in valuations that hide their real worth.

"These are companies with little or no coverage, so there's very little liquidity. So often times you will see opportunities in that space," says Ahuja. "They could be temporary dislocations, or companies that have had a temporary stumble that they will recover from over a medium to long term perspective."

Identifying an investment opportunity can be easier with a public company than a private one, since more of its financial information is readily accessible. But investors warn this is not an unadulterated benefit. The other side of publicly available information is that promoters of public companies are often less willing or able to provide access to internal information than private company owners are. Even having the needed financial information is no substitute for building a trusting relationship with the company's management.

Executing the deal often requires similar skills to any other PE transaction. At typically low liquidity levels, finding a seller willing to part with a significant stake can be difficult, so GPs often must go to the company's management, who usually hold 50% or more of the company anyway, to negotiate a fresh offer of shares.

In these cases PE investors say there is often little difference between their approach to private companies and these technically-public ones. Owners must be convinced that a GP can serve as a suitable partner for the company's future plans and that the relationship can be mutually beneficial.

An added layer of complexity comes from the inability to sign a contract for the investment and thus set up the kind of rights and protections that a PE manager might take for granted. Samena's Gupta points to Dynamatic as an example of how a deal without such arrangements can still work out to the benefit of both parties, but adds that the GP must demonstrate its willingness to help the target company and its trust in the management.

"We haven't signed any kind of agreement with them, but they invited us to sit on the board. And the reason is because they see us as long-term partners, they see us opening other markets for them, they see the value add that we bring to them in terms of understanding and deep diving into their operations," says Gupta. "All of these are reflective of the more traditional private equity approach to operational enhancement in the underlying company."

The relatively thin line between private and public companies in the Indian market means that in some cases GPs are on familiar ground with investees whose mindset is largely more similar to private companies than public ones. Subbu Subramaniam, founder of MCap Fund Managers, recalls a deal in which the firm paid $5 million for a stake in a listed company that brought its overall valuation post-investment to $30 million.

"If that isn't a private transaction I don't know what it is," says Subramaniam. "We got two board seats and 15% of the company. It's theoretically listed and continues to be listed, but you can't get out of 15% in one go. That is classic private equity."

Weaker flow

Though these borderline-private companies are a rich resource for GPs, they are not a renewable one. Investors acknowledge that finding such opportunities has become more difficult in recent years, accounting to some degree for the slowdown in PIPE deals both overall and as a share of overall deal flow.

Prejudice by LPs against PIPE deals has also played a part in the decline, with GPs reluctant to pursue too many such transactions for fear of alienating investors, many of whom hail from other jurisdictions and may therefore not be as familiar with the particular available in India's public markets.

"There will be a few LPs who say, ‘We're agnostic – as long as the manager is disciplined and the track record has demonstrated that they're using the flexibility smartly we'd love to give them more,'" says ChrysCapital's Ahuja. "But by and large the majority will say, ‘It's unconventional and it's hard for me to sell it internally, and so we wouldn't want to do something like that.'"

It is important to note that many LPs do recognize the role that PIPEs play in the Indian market and are not wholly averse to exposure to this segment, albeit in a limited way. The challenge from an institutional investor's perspective is to make sure a manager is using its money in the most responsible manner possible. CDC, for instance, specifies in its LP contracts that GPs may consider public market transactions if certain conditions are met.

"We want them to take significant stakes and be able to add value to those businesses. It might not be in the governance, because they might not get the right to be able to do that, but in terms of introducing new clients or enhancing their financing structure, or areas where they can add value," says Murugappan. "Only in those situations would we permit them to invest in PIPEs."

LP concerns have been allayed to an extent by the recent decline in PIPEs – with public market transactions making up less of the overall deal flow and a smaller part of the pot as well, the hope is that private equity firms are moving toward a more balanced approach. At the same time, GPs that pursue PIPE deals say they have seen a growing acceptance of India's PIPE potential among their investors, particularly those who have seen consistent positive returns from the strategy.

Indeed, it may help for GPs to build a certain level of flexibility in their fund structure. Samena, for instance, has set up its second fund so that returns from public market exits can be recycled for investment in the vehicle's other portfolio companies rather than being returned to investors right away. The firm believes LPs approve of its PIPE investments because of the higher returns that this strategy can provide for them.

Despite this flexibility Samena has done few PIPE deals in India recently. Gupta acknowledges that the firm has had a harder time finding the proper opportunities, partly because PIPEs form only part of its strategy so there is less risk of pursuing sub-standard public market investments for the sake of getting capital deployed. At the moment the GP is content to wait and see when the types of deals it wants will materialize.

"Tomorrow if things become much more attractive, we would be more than happy to deploy capital in them. It's just that valuations in our mind are far ahead of where they should be, especially in some of these hot sectors," he explains.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.