Australia aged care: The golden years

Australia’s aged care segment continues to appeal to private equity investors. But GPs must be wary of the challenges posed by the government’s unique stake in the market

"We knew at the time there'd been a number of investors looking to capitalize on opportunities in the space, but no one had really managed to crack the nut, as it were," recalls Tomás Chubb, an investment director at Archer Capital. The GP saw its planned acquisition of property group Lend Lease's aged care unit in 2013 as an opportunity to break open a market where private equity investors had made little headway.

Archer paid A$270 million (then $276 million) for the business, which at the time managed 30 facilities with 2,300 beds across Australia, and later changed its name to Allity. More PE deals in Australia's aged care space did follow: Quadrant purchased Estia Health later that year and New Zealand Superannuation Fund (NZ Super) acquired RetireAustralia in 2014 in partnership with Infratil. More recently, Advent Partners invested in W&L Holdings and Bain Capital Credit bought Craigcare.

However, these deals, which could be counted on one hand, represent AVCJ Research's entire record of PE activity in the Australian aged care market since 2010. Despite the previous examples, little momentum has built up, with market watchers citing obstacles such as uncertainty around government attitudes. While aged care assets remain attractive, any investment will have to be balanced by an eye toward policy.

Demographic pressures lie at the heart of the aged care thesis: Australia's population is growing older and living longer. The Department of Treasury projected the share of Australians aged 65 and older will reach 23% by 2055, with the population over 85 expected to double to 5% from 2% in 2014. Over the same period, life expectancy at age 70 is expected to grow from 17 years to 21 years for men and from 19 years to 23 years for women.

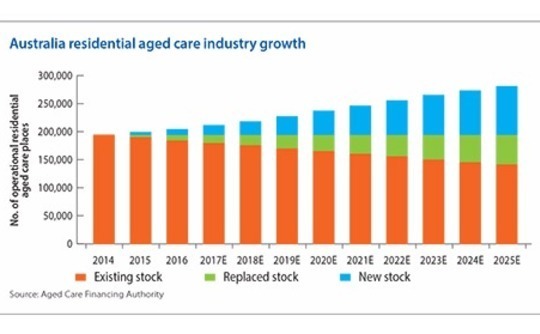

To meet this coming challenge, a 2015 report by the Aged Care Financing Authority (ACFA) estimated that the country needed to add another 82,000 residential aged care places by 2025, along with replacing nearly 50,000 existing places out of around 200,000 available as of the previous year. The total cost of this buildout has been calculated at A$33 billion.

This growth prescription poses a daunting challenge. Historically, the bulk of residential aged care services have been handled by non-profit agencies such as UnitingCare, the Uniting Church in Australia's charitable network. These players accounted for 52% of the residential care segment in 2014, compared to 37% for private operators and 11% for the government. But many doubt that providers whose focus is primarily charitable can support the kind of aggressive expansion that the industry needs.

"There's scope there for both for-profit and not-for-profit operators, but the onus is somewhat on the not-for-profit operators to perform with the same efficiencies that the private sector typically can," says Matthew Latham, a Sydney-based partner at Jones Day.

Rebalancing phase

Recent years have seen a shift in the aged care industry's center of gravity. Since 2010 private operators have added more beds than non-profit agencies in every year; the largest such gap occurred in 2014, when private operators added 3,372 beds while non-profits added just 211. For-profit providers also outdid non-profits in the latest Aged Care Approvals Round, taking 63% of the nearly 11,000 licenses awarded and accounting for nine of the 10 largest allocations of residential places.

Rather than a retreat, non-profits are undergoing a rebalancing, focusing on the remote areas that private operators tend to avoid and leaving cities and suburban markets to their for-profit counterparts. This reflects a widespread belief that the non-profit sector will continue to play a vital role in aged care, which is still seen primarily as a public service that should be available for all rather than an area for private owners to make money.

This realignment will not address the underlying demographic concerns, however. The added beds still represent a fraction of what is needed, even combining the private and non-profit sectors – especially considering that the government has closed some of its own aged care facilities over the same period, representing about a third of the beds added by the other two. Moreover, the market remains highly fragmented, with over 1,000 providers handling more than 189,000 places, creating inefficiencies in delivering care and complicating regulators' efforts to oversee the industry.

In such a fragmented market, a backer that can enable consolidation would have considerable opportunity, and this has driven much private equity interest in the space. The year after Archer's acquisition of Allity, the company bought a portfolio of aged care homes and a retirement village owned by ECH, and at the time of its 2014 IPO Estia was aiming to become the fourth-largest domestic aged care player through a series of acquisitions.

But regulatory action over the last few years have complicated matters, sending out mixed signals regarding private players' freedom of movement in the industry. For example, last year's guidance on service fees from the Department of Health seemed to rule out the ability of private operators to charge a range of fees for additional services. Many investors were left wondering how reliable their revenue predictions could be if they were likely to be subject to such interference in the future.

Uncertainty over revenues has been compounded by concerns over changes to the government subsidies that have historically made up a significant portion of aged care facility operators' funding.

While the government has not lowered the subsidies in absolute terms and in fact has continued to raise them, the increase has not kept pace with the rise in beds. When operators like Estia, Japara Healthcare and Regis Healthcare went public in 2014, their financial disclosures revealed how much they took in from the government, which soured public sentiment against them to an extent.

"It's kind of a Catch-22 when they go out and list and talk about how much they make," says Adrian Arundell, managing partner at Azure Capital, which advised on Bain's acquisition of Craigcare. "They're kind of waving the flag in front of the government's face, saying, ‘We're doing well,' which causes conservative politicians and fringe voices in the political sector to put pressure on funding."

These regulatory and funding issues are not necessarily a deal breaker for investors, which are looking to build companies that can survive independently in a strong private sector and would therefore be unlikely to invest in players fragile enough to be brought down so easily. Moreover, the existence of such players is a source of security for investors operating on a larger scale.

"We were confident that the government would never be able to do anything too severe, on the basis that it would put a lot of these smaller guys out of business and then they'd have real problems on their hands," says Archer's Chubb.

Public problems

Despite this confidence, industry participants acknowledge that the space has been challenged lately. Following ballooning valuations over the last two years, listed companies in the industry have all dropped back down in recent months. Estia, the only formerly PE-backed operator, is the worst of the lot: after opening at A$4.98 in December 2014, its price as of the last close was A$2.82.

Investors caution against reading too much into this performance, however, noting that Estia in particular has had a number of factors working against it that might not apply in other cases, such as questions around how it would pay back the debt it took on for its planned acquisitions. By contrast, Japara is holding steady near its IPO price, while Regis is significantly higher, though both have dropped considerably from their peaks in 2015.

For some, the real lesson is that public markets are not the best custodians of aged care operators. Though demographics make them a solid long-term bet, their reliance on the vagaries of public policy means that there will always be questions around their short-term performance, leading to wariness among investors.

While IPOs may of necessity continue to be the best exit option for the near future, investors in this space should be mindful of other opportunities. NZ Super's RetireAustralia purchase is seen as a possible indicator of the market's future: the sovereign wealth fund has the patience to see its investment through short-term ups and downs and experience with a market that's already gone through the transformations needed in Australia.

"The New Zealand and the UK markets are where everyone's taking a lead from, particularly in aged care," says David Willis, Australia private equity leader at KPMG. "Those economies went from an 80% not-for-profit to an 80% for-profit balance, and that's where we think Australia will end up going too."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.