India consumer: Beyond the box

GPs are finding India’s packaged food and beverage sector increasingly attractive, but only companies with the right mindset are likely to thrive under private equity partnership

In 2008 Motilal Oswal Private Equity (MOPE) had just raised its debut fund and was looking for investments that would set the firm apart from its peers. Parag Milk Foods was an obvious choice: the dairy industry had huge growth potential but few investors had ventured into the space, unconvinced there were businesses that could be scaled.

"Dairy is the largest consumer food item in the country, but at the time more than 90% was still in an unorganized form," says Vishal Tulsyan, managing director and CEO of MOPE. "We believed people wanted quality and convenience, and we believed they wanted it in packaged form."

MOPE committed $14 million to Parag, made a partial exit to IDFC Private Equity in 2012, then sold the rest of its shares when the company went public last year. Spurred by an overall money multiple of 4.5x, the GP has made more investments in India's packaged food and beverage space. Other investors have followed, sending the amount of private capital in the industry to more than $1.1 billion over the last 10 years.

While packaged food and beverages are seen by many as an exciting bet, industry players warn against simply following the crowd. Successful investment hinges on an understanding of the target company's strengths and weaknesses and how it fits into the broader Indian consumer story – as well as making the case to sponsors and management on the benefits one's involvement can bring.

Slow start

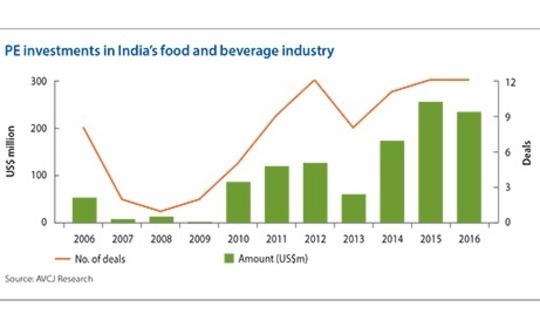

For many years, private equity interest in India's packaged food and beverage space was moribund. Before 2006, AVCJ Research has no record of any activity at all, and even once GPs started deploying capital, the sums were paltry: Between 2006 and 2009, only 13 deals were announced, with less than $80 million in aggregate commitments.

However, 2010 launched a period of significant growth. Five deals were recorded that year, totaling $87 million – more than the previous four years combined – and the level of investment continued to climb until 2015, with the exception of a dip in 2013. Last year, the total fell slightly to $233 million from $254 million in 2015, but the number of deals announced remained the same.

The youthfulness of the Indian market is another consideration, with a median age of 27.6 and 45% of the country's population under 24 as of 2016. As this cohort ages, not will consumption rise but it will also become more sophisticated, with food and beverage choices far removed from those of their parents and grandparents. In particular, issues of health and sustainability are expected to grow in importance over the coming decades.

"The Indian consumer today is not the same Indian consumer as my parents," says Ash Lilani, co-founder of VC firm Saama Capital, whose investment focus includes the non-technology consumer sector. "The Indian consumer today is exposed to global media. They see global TV, they are on the internet, and they know which products are currently en vogue across the world. It's easier to educate them on cold-pressed juices or Greek yogurt."

Investor fatigue with other areas of the food and beverage space may also play a role. Nishesh Dalal, co-head of transaction services at KPMG India, points out that the surge in packaged food and beverage investments began soon after PE activity in the food services and restaurants space began to decline from the 2008 high of $493 million. This suggests that as sentiment soured on this segment, investors began to seek more attractive targets for their capital.

"The general sense now is that very few investors have really made money from food services and restaurants," says Dalal. He observes that restaurants can be a lucrative model for owners and operators, but financial investors may have a hard time finding attractive returns due to the added expenses of building scale.

By comparison, the cost base for packaged foods companies is much more predictable and consistent. A single factory can satisfy demand for an entire state or region, and can also reduce manpower costs since workers can often be drawn from the semi-skilled or unskilled population and need not be replicated across multiple locations.

Nevertheless, as attractive as the packaged food and beverage sector might be at first glance, it is not without challenges. Many companies can efficiently produce high-quality food products, but this alone is not enough to bring the kind of returns that PE investors need.

For example, Saama's investments in the sector include cold-pressed juice producer Raw Pressery and specialty food ingredients maker Veeba. It intends to support niche players like these in the early stages and help them build their consumer appeal. As such, entrepreneurs must have the will to move beyond their current stage of development.

"What we find with our food consumer guys is they're obsessed with quality, they're obsessed with innovation, but also they all have other ideas, how to enter different verticals over time and build up a much larger company," says Lilani. "If you look at Veeba, every six months they're launching a new product range, and each one is cumulative to the previous revenue base."

Private equity firms, which get involved at a later stage than the likes of Saama, face additional obstacles. The principal danger is a founder will have reached a certain level of success and be content to stay there. A classic example in India is a business with a comfortable level of revenue in a particular state or region and no motivation to make the effort required to become a national concern.

Another issue is making sure an investee company is able to work with a private equity partner. Several investors note that entrepreneurs are often reluctant to get involved with financial sponsors, who they fear will not understand the business and make disruptive and unproductive demands. It is incumbent on the GP to convince the company's leadership that they represent an opportunity rather than a threat.

"Once they're familiar with our approach, they realize they are the biggest beneficiaries, because private equity may take a minority stake, but the majority stake remains with the sponsors, and as a result they can make the best of it," says Girish Nadkarni, a partner at IDFC Private Equity. "If the company does well because of the private equity approach, the promoters are the ones who stand to benefit over the long term."

The way out

Exit opportunities in the packaged food and beverage space are still developing. MOPE is one of few GPs that has been through the full investment process with more than one company. In addition to Parag, it secured an exit from Cremica – a producer of condiments and snacks that spun out from Mrs. Bector's Food Specialties – when Rabo Equity Advisors bought the business last year.

However, the Parag and Cremica situations underline the appeal of public market and secondary exits for such businesses. Trade sales are the missing piece, but investors believe global strategic players will eventually arrive on the scene, attracted by India's developing consumer market and buying a local player to take advantage of the opportunity.

Given PE's reputation for professionalizing the management and tightening up the financials of mid-cap businesses, portfolio companies would make for natural targets – but achieving this kind of exit is conditional on the majority shareholder being of the same mind.

"We have seen a change happening in the mindset of Indian entrepreneurs, where they feel that after this stage they probably would be willing to sell it to any large global player," says MOPE's Tulsyan. "The entrepreneurs played a big role in taking the company from scratch to a particular level, and to go from that level to the next level, getting a large global player to come on board could be interesting."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.