Japan succession deals: The long game

Succession planning opportunities are growing in Japan’s middle market as a generation of founders bend to the will of time and commercial pressure. For GPs seeking buyouts, it is all about who you know

With a network of 295 regional financial institutions, 660 accounting firms and a couple of thousand individuals, Nihon M&A Center claims to reach deeper into the heart of corporate Japan than any other intermediary. The Tokyo-listed company has seen its revenue more than double over the last four years from fees accrued by working on transactions involving small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

The deal count for the 2015 financial year came to 420, up 24% on the previous 12 months. Between January and March of last year, Nihon's mandates ranged from a merger between two food wholesaling businesses in Okinawa to the acquisition of a Greater Tokyo packaging materials manufacturer by a private equity fund. The number of consultants dispatched to develop M&A activity on the ground has also risen, nearing 200 by the end of 2015, twice the total from four years ago.

Succession planning deals involving founders who are nearing retirement and have no heir within their family are the lifeblood of Nihon's business. The company is readily identified as of one of the most aggressive advocates of these transactions, part of an ecosystem with banks at one end and small-scale boutique advisors at the other. These groups may compete or collaborate, all with a view to tapping Japan's growing succession opportunity.

PE firms are willing buyers, but founders are only just getting comfortable with the notion of selling to them. "Founder-owners often say, ‘If I sell, it should be to a trusted company in Japanese society like Mitsui or Mitsubishi Group,'" explains Toshiyuki Mitsuzawa, managing executive officer of Frontier Management, a boutique M&A advisor. "Mid-size companies are second choice and private equity third. Even now PE firms are seen as aggressive by employees, although the market is changing little by little." PE investors acquired 20% of the 50 or so SME transactions his firm completed last year.

Growth might be from a low base, but it is undeniably taking place. Advantage Partners, for example, made seven investments during the year ended October 2016, six of which were rooted in succession planning. Richard Folsom, the mid-market GP's co-founder and representative director, ties it to that same change in perception; he believes it started about four years ago and is happening faster than Mitsuzawa suggests. Advantage has closed 16 deals since 2013 and only four of those haven't been founder succession.

"Once that sense of the value private equity can contribute takes hold, usually by word-of-mouth, it can move quickly – we are talking about single decision makers who with a change of heart and mind can act much faster than a big corporate with a divestment," Folsom says. "Private equity is doing 30-50 succession deals a year, so it is only making a small dent in the larger population of companies that are going to run into problems if they don't find the right solution."

A bumper year

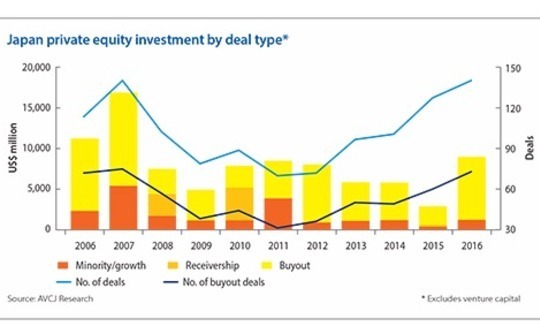

Advantage's seven deals represent the busiest year in the firm's history. The story is much the same for the industry as a whole. According to AVCJ Research, private equity investment in Japan (excluding VC capital) came to $9 billion, three times the 2015 figure and the largest annual total since 2007.

Now, as then, several large-ticket transactions have a disproportionate impact on the headline numbers. The stand-out from the class of 2016 is KKR's agreement to purchase Nissan Motor's controlling position in automotive components supplier Calsonic Kansei Corporation and subsequent $4.5 billion tender offer for the entire business. With Japanese conglomerates under assorted regulatory and commercial pressure to divest assets, the Calsonic deal would lay down a marker for an expected uptick in activity.

The impact of smaller succession deals is reflected in transaction volume. AVCJ Research has records of 141 deals in 2016, once again the most since 2007, and 73 of these were buyouts. Kazushige Kobayashi, managing director at Capital Dynamics, puts the number of buyouts at approximately 80, up slightly on 2015, with succession deals accounting for about half (others say it is even higher). "It's getting better and we expect more this year," he observes.

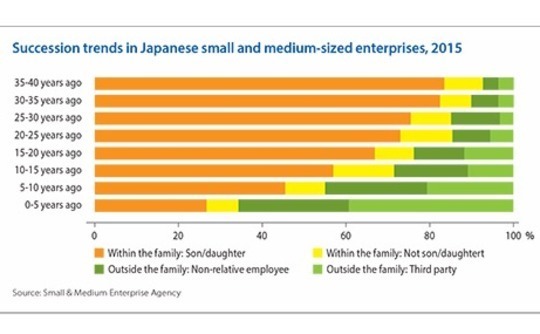

SMEs account for 99.7% of the enterprises in Japan and 70% of employment, according to the Ministry of Economy, Trade & Industry (METI). Over the last 20 years, the average age of the SME founder has increased from 47 to 66. Moreover, 20 years ago, three quarters of companies would stay within the family as control was passed from the founding generation to the next. Now only about one third follow this path; close to 40% go to third parties with no ties to the family.

The two investments completed by Tokio Marine Capital last year – integrated manufacturing specialist KEC and chilled desserts manufacturer Ropia – make for fairly typical scenarios. In the first case, the son was unable to succeed his father due to ill health, and in the second, the son was unwilling to assume the leadership role, prompting a sale process due to the absence of other suitable heirs.

"It is not unusual for children to be reluctant to succeed their parents," says Frontier's Mitsuzawa. "Some of these companies are old-fashioned with limited growth, a lot of employees, and potential issues on the horizon. Another big issue when succeeding as controller of a business is you have to provide personal guarantees for the debt, and many younger people don't like that."

These guarantees are also one of two major stumbling blocks to succession in the absence of a clear plan. The loans are fully collateralized, which means once a founder passes away, their life insurance pays down the principal. However, many SMEs have debts that far exceed the provisions of these policies, so the children must negotiate with banks before they can consider a sale. The second obstacle is revisions to inheritance tax policy introduced in 2014, which not only increased the base rate but also eliminated many of the deductibles that meant some families didn't pay any tax at all.

"Private company shares are not accepted in lieu of tax payment, so the family needs to monetize the shares. If the children have no interest in running the company they use the shares as collateral for bank loans, pay the tax, and appoint new management. In many cases, performance deteriorates in the absence of the founder and the shares are seized by the banks," says Megumi Kiyozuka, managing director, CLSA Capital Partners. "This is one of the reasons why ageing founders are considering sales."

Sourcing issues

Nihon identifies its target market as approximately 600,000 SMEs with annual sales of JPY100 million ($885,000) to JPY2 billion. This narrows to 180,000 when companies without suitable profitability are excluded, and of these, 120,000 are estimated to have no defined successor. Others have their own qualification criteria, although it is said that few GPs would consider buying a company with under JPY1 billion in EBITDA. Even when the results are pared, SMEs represent a widespread and hard-to-access corporate subset.

The larger private equity firms with an on-the-ground presence in Japan have their own sourcing networks. Bain Capital Private Equity, for example, has completed 12 Japan deals of at least $100 million in enterprise value, of which 4-5 involved succession. The vice chairman was formerly a senior executive at SMBC Nikko Securities and his main function is cultivating relationships that could deliver transactions. In addition, there is a group of about 10 senior advisors who trawl their own networks for deals.

The Carlyle Group also prefers to approach family owners directly, only relying on lawyers, accountants or other acquaintances when there is no other route. Succession planning accounts for about half of its Japan investments, including two out of three deals announced in 2016. Each one – bean sprout producer GGC Group and Money Square, a provider of foreign exchange and index investment solutions – took two years to develop, although the average is 3-5 years.

"These days most families have a basic knowledge of private equity but the most important aspect is showing how we can add value," says Kazuhiro Yamada, managing director and head of the Japan buyout team at Carlyle. "Before we make contact we analyze the industry and company, identifying improvement initiatives. Approaching the appropriate person and building a relationship takes time as well, but once we have made our presentation to the key man it becomes easier."

David Gross-Loh, managing director at Bain, recalls spending three years establishing common ground with Hiroshi Hashimoto, founder of hot spring chain Oedo-Onsen, before acquiring the business in 2015. This involved formal business proposals and site visits plus social interaction intended to help Hashimoto understand the GP and its culture. The founder also conducted his own due diligence, speaking to the CEOs of other Bain investments in Japan.

"It took a long time relative to the average private equity deal cycle, but he was happy with the transaction and now serves as a reference for us, making calls to people in his network who may also own companies," Gross-Loh says.

Mitsuzawa describes a similar process at Frontier. The company has a business succession team of more than 15 former bankers whose job it is to leverage their networks within the regional lenders in search of referrals to potential deals, while an eight-strong business development division looks to work with banks on a more formal basis in meeting borrowers' succession needs. Another sourcing channel is founders who approach Frontier themselves.

When first engaging in discussions, the focus is general strategy; eventually a founder might say they have "something to consider," typically a coded reference to succession. Establishing trust, eliciting that admission of the challenge facing the company, and guiding them to a position in which they are comfortable with a sale could take anything from six months to two years.

If the intermediary is able to do much of this legwork, when a PE firm gets involved it might take six months or less to close a deal. There are hundreds of boutique advisors in Japan, typically established by ex-investment bankers or securities company executives who provide ongoing services to longstanding clients in particular industries. Founders are often closer to these advisors than their bankers, in part because they are more independent-minded than banks.

For mid-market private equity firms, relationships with intermediaries can be just as important as those with the target companies. Advantage tracks 136 intermediaries in total – the definition encompasses the likes of financial advisors and brokers – and categorizes about 23 as tier one, based largely on its frequency of engagement with them. CLSA has live relationships with at least 40-50. There will be regular communication between GP and advisor. This might include an ongoing longlist of potential targets for the advisor to monitor.

"The critical question is: When these intermediaries identify opportunities, which private equity firms do they call first?" says CLSA's Kiyozuka. "We continue to approach sellers directly, but it is rare to find a direct channel before they start a sale process. It helps to have good relationships with intermediaries. They don't have the bandwidth to run fully-fledged auctions so they want to close deals as efficiently as possible, as proprietary deals or limited auctions. We refer to them as our ninjas."

Valued partners

Careful sourcing is becoming even more important given how the succession planning opportunity is evolving. Age is not the only issue. A generation of younger founders are open to the possibility of selling up in order to pursue other business interests. At the same time, companies face more challenging commercial conditions before, notably labor shortage, and in some cases the need to pursue consolidation domestically or expansion internationally. In this context, seeking out a partner with capital and experience makes sense.

Hiroto Nakayama was still in his 30s when he sold Asiro, an online marketing platform for the legal community, to J-Star last year. Nakayama had no intention of standing down as CEO but appreciated that an external shareholder would instill good governance in the business and help it achieve scale. "We sometimes still question why he sold a majority stake because the business is solid," says Greg Hara, CEO and managing partner at J-Star. "But founders do this so they can utilize our ability to take a company to the next level without having much of the risk."

All six portfolio companies in CLSA's current fund came out of succession situations and five are structured as joint ventures in which the founder retains a minority interest. Advantage saw this phenomenon emerge in 2014 when it acquired an assisted living facilities company in Hokkaido from a founder who was 39. A call center business in Osaka set up by an entrepreneur also in his 30s soon followed through the same advisor, and there have been similar transactions since then.

The unifying factor in all these investments is a recognition of the value that private equity can bring in delivering growth. It is a sentiment far removed from the suspicion that hung over the industry as recently as 10 years and investors attribute the change to their track record.

"When we started in 1998 our main targets were carve-outs and distress situations. Family entrepreneurs didn't know about our activities and we didn't pitch them," says Koji Sasaki, a partner at Tokio Marine Capital, which has since completed 10 succession-related deals. "The biggest reason for the increase in succession transactions in recent years is that private equity in general is becoming more widely known. The success stories involving family businesses are piling up one by one."

However, the momentum is not all in one direction. A broader appreciation of the succession planning challenges creeping up on corporate Japan has made the issue a topic of discussion and a policy priority for the government. "M&A as a strategy" is now propagated by commercial banks that see it as a source of income from advisory fees, deal financing, wealth management services and even returns on private equity fund investments they make. For listed M&A advisors like Nihon as well, driving up transaction fees is essential to maintaining corporate value.

Private equity has to wind itself into these lines of communication, ensuring that sales to financial sponsors are part of the succession-planning conversation, even if acceptance is gradual. "Our pipeline is as full as ever and you do find in Japan that once one founder starts to do something, others study it and realize that course of action is not as risky as they once thought," says Bain's Gross-Loh. "It starts a rolling stone process – no overnight, dramatic change, but more incremental."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.