India renewables: Streams to rivers

Indian investors feel that despite recent problems with yieldcos on the global market, the model still holds promise for the country’s renewable energy sector

Two years ago, US-based renewable energy giant SunEdison was busy laying the groundwork for its downfall. While the firm trumpeted its newly launched subsidiaries, the "yield companies" TerraForm Power and TerraForm Global, a lack of discipline would ultimately seal its fate.

The operating model of the yield companies, or yieldcos, was still relatively new to investors, having been introduced only in 2013, but it seemed to offer promise: SunEdison would buy or develop renewable energy assets; after getting them in good working order, it transfer the assets to one of the TerraForm companies to manage; and the yieldcos would then pass most of the income back to investors, who could reap steady returns without most of the risk associated with renewable power.

Less than two years later, however, SunEdison's plans lay in disarray. Rather than relying solely on the income generated by the operating assets, the parent had committed to an ambitious acquisition strategy in order to augment the yield with steady growth. This approach backfired when the price of the acquisitions grew beyond the company's expectations.

"They needed to continuously feed the yieldco with new assets and create growth, and most of those acquisitions were leveraged," says one industry professional. "They would take on debt and purchase new assets, and as long as debt was available and cheap, it was possible to do this. But the moment debt stops or the debt becomes expensive, this model collapses, which is exactly what happened."

SunEdison's collapse and subsequent bankruptcy have reverberated across the globe, including in India, where interest in renewable energy has continued to build, and the country's PE-backed energy platforms had begun to consider the possibilities of taking advantage of the model for themselves.

The yieldco structure itself is still considered attractive for certain types of domestic investor, who could benefit from the stability and reduced risk that it offers, and private equity players see it as a potentially useful part of their investment strategy. At present, though, the consensus view is that renewable energy projects in India must show continued development, and viability, before the model can be effectively introduced.

Big targets

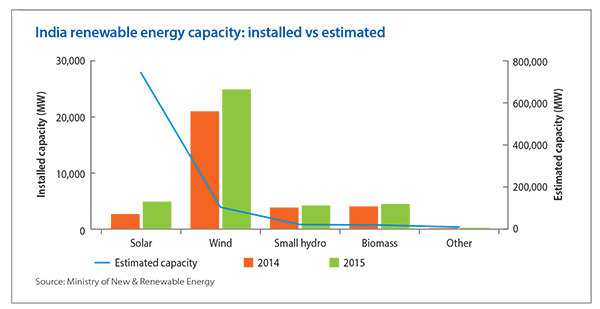

Those seeking exposure to the sector have a key ally in the country's government, which has made renewables a priority for its potential both to reduce dependence on imported energy resources and to mitigate the negative environmental consequences of coal-fired economic growth. The Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation estimated this year that India's total capacity for renewable energy generation could be as high as 897 gigawatts. Solar power is by far the largest contributor, with 84%; wind power accounted for 11%, while small hydropower, biomass and waste-to-energy collectively made up less than 5%.

However, installed capacity lags behind this estimate: about 39 GW of grid-connected renewable energy was in place as of March 2015, with wind accounting for 25 GW. To boost these numbers, the government has targeted 175 GW of installed renewable capacity by 2022, and implemented a number of incentives to encourage development, including a 10-year tax holiday for solar power projects and obligatory purchases of renewable energy by states.

Industry participants view government support as crucial to development of the sector. Nupur Garg, the regional lead for South Asia at the International Finance Corporation (IFC), points out that a number of players who were traditionally not involved in the energy sector, much less renewable power, have recently entered the industry.

Hero Future Energy, a clean energy-focused branch of the traditionally automotive-focused Hero Group in which IFC recently proposed to invest $125 million, is one such example: the company is planning to commission solar and wind energy projects with a total capacity of over 1 GW in the next year. The participation of investors with deep pockets such as Hero is seen as vital to building up the industry. "A lot in this sector is about getting to scale. Once you have a decent scale and the business is viable, it is much more attractive for private sector investment," Garg adds.

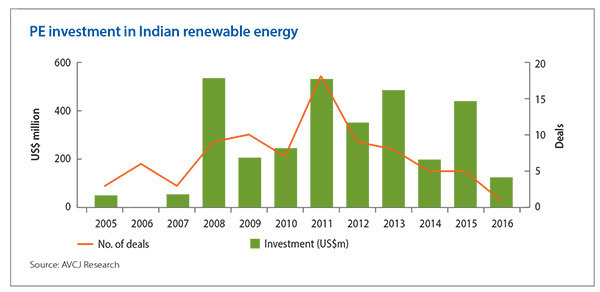

Private equity investors have shown increased interest in the renewable energy space in recent years; AVCJ Research shows more than $3 billion of investment across 84 deals since 2005. Deal volume reached a peak in 2011, when 18 transactions were recorded for a total of $527 million; despite the subsequent steady decline, the amount of capital committed remains relatively robust, exceeding $400 million in some years.

It is a widely held view that yieldcos are a promising model once the industry has attained a level of scale and stability in operational terms. The structure would give private equity investors that are currently building and operating platforms of renewable energy assets more flexibility in managing them while still generating income for their LPs.

For their part, institutional investors could reap the benefits of a stable, low-risk revenue stream, since yieldcos are also attractive because they involve only completed energy generating facilities with contracts already in place. Price volatility is also less of a concern since the assets do not need fuel.

Obstacles to adoption

However, while several investors have expressed interest in converting their energy assets into yieldco structures, there are a number of factors holding the model back from implementation. The structure's checkered history on the global stage is one; SunEdison's bankruptcy highlighted the risks that can come when a manager seeks returns through fast growth rather than careful curation of the underlying assets.

"When the yield is just 3-5%, then you can't live with that small return, so you have to find growth. If you keep the yield at a higher number, 7-9% for example, then the investors may not need growth, and then you don't get into that kind of aggressive behavior," says one investor. "SunEdison just went overboard trying to be very aggressive in terms of the yield for immediate benefit, and therefore they needed to feed the growth."

Achieving that kind of return purely from operational assets can be an intimidating thought. Greenko, the India-based renewable energy platform that was listed on London's AIM board until last year when GIC Private acquired the asset, agreed to the takeover precisely because it felt that its share price did not fairly reflect its performance, which observers attributed in part to low investor confidence in India's energy sector.

Investors involved in the sector acknowledge that there are grounds for skepticism. Construction quality of energy assets is a constant concern for potential investors.

"We've seen wind turbines built where the turbines are literally on the wrong mast, turbines have caught fire or the mast has toppled over, because of poor workmanship in the construction or just poor quality turbines," says David Russell, CEO of Equis, which has developed more than 800 megawatts of wind and solar capacity in India. The difficulty of ensuring construction quality is why Equis does not buy finished assets; the GP's renewable energy portfolio is composed entirely of projects it has developed itself.

"You can certainly due diligence the equipment that's been installed and the quality of that equipment, but you can't due diligence, for example, how a wind mast foundation has been constructed, how the concrete's been poured, and whether there's been the right reinforcing, because it's built, it's covered up, and you're just going to inherit whatever the guy sells you," Russell adds.

Quality concerns with renewable energy assets extend beyond construction, too. For example, wind power is considered unreliable compared with solar and hydropower; the unpredictable nature of wind flow make accurate projections of power output and revenue generation near impossible.

Investors also worry about the ability of yieldcos to ensure that customers pay them as agreed. The power generators must sell their energy to distribution companies, or discoms, whose reliability in delivering the agreed payments can vary widely. A combination of effective due diligence to identify buyers likely to be problematic, and hedging against the possibility of late payments, is needed to account for this risk.

"Sometimes these discoms run into liquidity issues and the payments get delayed," says Mayank Choudhary, an investment professional with the Asian Development Bank. "That cannot work in a yieldco model, because you need to get the income to the investors; you can't let your payments get stuck. So that needs sorting out."

The various challenges attending operation of renewable energy assets in India are one reason why the model has so far failed to take hold in the country. Another contributing factor is the lack of projects that are suitable to such platforms. Existing platforms have so far focused on development of renewable energy assets rather than operating them; this may change as they build up their portfolios and their experience in the sector, but at this stage investors feel the market has not reached the maturity needed to make the structure viable in India.

Institutional appeal

Nevertheless, once a pool of assets has been built up, yieldcos could offer considerable appeal to Indian energy players. The structure is seen as particularly suited to domestic institutional investors, such as insurance firms and pension plans, which look for reliable streams of income rather than high financial returns.

Domestic energy platforms like GIC-backed Greenko or Goldman Sachs-supported ReNew Power Ventures, both of which recently raised capital from the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, could use the model to split their operational assets from those that are still in development, and offer the revenue of the former as an investment product. If the vehicle offers suitable returns - investors feel a rate of 7-10% is the most attractive - then attracting local institutional money might become a realistic prospect.

This appeal does not extend to foreign institutional funds, which are likely to be turned off by the necessary losses to exchange rates - which is not a factor for domestic players - and the inherent risk in the underlying assets. Even investors that are otherwise active in India might conclude that the combination of these factors reduces the likely return to the point where other products, such as corporate bonds or government debt, appear more attractive.

Converting a platform to a yieldco opens a number of possibilities; investors can treat the conversion as an exit, particularly if the resulting entity ends up listed. This could represent an opportunity to dispose of assets that are otherwise tied to multi-year contracts that extend beyond the life of the PE fund.

"Given the right pool of assets with the right returns, you could think about moving this to a yieldco and using the capital that you get to either give yourself a return on your investment or to invest in further growth," says Bhavik Damodar, COO of infrastructure and government services at KPMG India.

Private equity firms that maintain their own renewable asset portfolios can also take advantage of the model to give themselves more flexibility in terms of management and how money is returned to investors. Rather than keeping all assets in its investment fund, which would need to be exited after five or so years, the GP can spin out the best-performing projects into a separate vehicle that continues to deliver revenue on a long-term basis; this can help it satisfy different types of LPs.

Those that wish for quick exits can achieve this goal through the main investment vehicle, while those that want steady, reliable returns can attain them through the yieldco structure.

"Is an investor looking for a yield from the projects, or are they more capital return-focused, looking for you to build and sell, and either recycle that capital into new projects, or just recycle the capital out?" Equis's Russell says. "If you fall into the latter, then maybe you're building and selling, but if you want to continue operating those projects, maybe you've got to create a separate yield or income-focused vehicle: one pool of capital that's focused on operating projects, and another pool with a different cost of capital attached to it that's focused on the development and construction risk of those projects."

Since stability is key to the appeal of a yieldco, managers must be careful about the quality of what they feed into the platforms. Adding large groups of assets at once should be avoided, since this can reduce the time available to examine the projects and any underlying flaws can cripple the entire vehicle. The age of the assets should also be considered. Newly constructed projects that have not had time to work out operational issues could produce unexpected problems later on, but the longer an asset is in operation the less time remains on its contract and the less value it ultimately has.

While the still-nascent stage of development in India's renewable energy sector is likely to delay implementation of the yieldco model, investors believe the structure does have potential over the longer term. The country's growing interest in clean energy, and the number of developers entering the space, mean that the number of assets coming online will continue to grow, and with it the need to take full advantage of the revenue streams they generate.

"We haven't really gotten to the stage where we've got assets to be monetized; we're just scaling to that cycle now," says KPMG's Damodar. "Now that we've seen the early rounds of investments, which are now coming up for monetization, that's where we are seeing a lot of interest."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.