India NBFCs: Lending a hand

Momentum is building among India’s non-banking finance companies, and PE, government and regulators see promise in the power to reach untapped markets. Success will require the support of all three parties

Earlier this year, Sandeep Aneja, founder of education-focused Indian GP Kaizen, was faced with an important decision. He had passed on Varthana before, when the non-banking finance company (NBFC) - which lends to many small private schools that are not served by India's traditional banks - was raising its Series A round in 2014. Back then Kaizen concluded the company was not mature enough; but what about now?

Aneja decided to take the plunge, co-leading the INR930 million ($14 million) Series B round with Zephyr Peacock India. He was not only convinced by Varthana's track record, but also encouraged by the founders' expertise; their background in education gave the company an edge over other, non-specialized lenders.

"Varthana will always be distinguished from a generalist NBFC lending to schools, because it understands the education sector really well," says Aneja. "The credit process of Varthana is not dependent entirely on understanding the values of the non-performing assets, or the loan to book ratio, but it is dependent much more on the quality of education."

Kaizen's Varthana investment is one example of the many approaches that private equity firms have taken to India's NBFC industry. Strategies have evolved along with NBFCs themselves, with early generalist participants being joined later by more narrowly focused lenders and investors. Industry participants says this segment of financial services can deliver considerable opportunities for investors able to keep pace with its development.

Rising star

NBFCs have become an increasingly prominent part of India's financial sector. A report by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) published last year shows that the NBFC share of the overall credit sector rose from 10% in 2005 to 13% in 2015. This increase in market share is even more pronounced for narrower segments such as home finance, where NBFCs went from 26% to 38% between 2009 and 2015, and commercial vehicle loans, with growth from 42% in 2013 to 46% in 2015.

Overall, loans from NBFCs have more than doubled over the past five years, increasing from INR5 trillion in 2010 to INR12 trillion in 2015. This rapid growth is expected to persist, since NBFC credit is just 13% of GDP in India, compared with 26% for Malaysia, 33% for China and 74% for Japan.

This expansion of NBFCs as an element of India's credit sector has been attributed to several strengths of the model, compared to traditional banks. One major difference is the lower investment required to build new branches. Banks, which typically offer a wider range of products than NBFCs, have correspondingly greater infrastructure requirements, making it less economical to set up offices in some geographies than in others.

"I've seen NBFC branches that are literally four walls, no air-conditioning, two tables, two computers and that is it," says Bhavik Haithi, managing director at Alvarez & Marsal. "A bank branch can't operate without construction and infrastructure, and NBFCs can save those costs and pass them on."

Some unique features of India's market have also contributed to the NBFC growth story. For one thing, the rapid growth of the country's economy has created a steady stream of lending opportunities among large companies; with India's banks focusing on these businesses, smaller companies have had a harder time attracting financing.

This creates a space into which NBFCs can step, and since their customers have fewer options than most credit seekers, the institutions have more control over the terms of the financing. Thus, though the cost of a particular deal may be higher for an NBFC than it would be for a bank, the NBFC can derive a better return than a bank could - particularly given that a bank would not have picked up the deal in the first place.

The small and medium enterprise (SME) market segment can also be targeted by sector-specific NBFCs, a more recent development in India's financial sector. These institutions are set up to pursue more narrowly focused opportunities, usually by leveraging the founders' expertise in particular areas to identify borrowers that have been overlooked by banks and even by other NBFCs.

Varthana is one example of this phenomenon: the company, launched by former teacher Steve Hardgrave and banking veteran Brajesh Mitra, assesses a potential borrower's chances for repayment based on the strength of its business. This approach is seen as more effective than a purely financial form of appraisal, partly because the borrowers often do not have an extensive credit history and partly because it sees the success of the underlying business as a better indicator of creditworthiness.

Avanse Financial Services, another education-focused NBFC that provides loans to students pursuing higher education, follows a similar approach. The company, which is backed by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), examines borrowers based primarily on their past academic performance and their likelihood of graduating and finding a job.

"The biggest mitigating factor to risk, and the biggest likelihood of them getting their money back, is if the student gets a job," says Kaizen's Aneja. "It is not as if they drag the parents' property down into a sale and find a buyer. That's a long drawn-out process; you may have covered your principal but the cost itself is prohibitive for a lot of NBFCs."

PE approaches

The ability of NBFCs to identify and assess lending opportunities in underserved populations is one factor in their appeal to private equity. Their potential for high returns, in spite of higher financing costs, is another. NBFCs' average return on equity (ROE) has beaten that of the banks in all but two of the last 10 years, and the average ROE for NBFCs over the same period was 15.7% compared to 14.1% for banks.

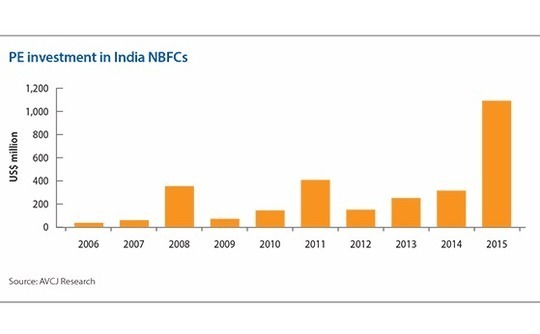

As a result, investors have piled in, committing nearly $3 billion in Indian NBFCs over the last 10 years. The level of investment has grown steadily in that time, despite periodic spikes - the last in 2015, when total commitments reached almost $1.1 billion, about double the investments in the previous two years combined.

That jump was the result of several larger-than-normal deals, including Bain Capital's INR13 billion commitment to L&T Finance Partners, the financial services unit of domestic conglomerate Larsen & Toubro, and a INR16 billion investment in microfinance institution (MFI) Bandhan Financial Services by IFC and GIC. These deals could be seen to represent the two poles in NBFC investing, but the space is even more complex. While some stick to straightforward equity investments, others set up their own institutions.

KKR, for example, has two NBFCs in India: a structured credit provider founded in 2009 that focuses on entrepreneurs, and a real estate-focused company set up last year with GIC Private as a lead investor. Pan-Asian special situations investor Clearwater Capital Partners has been involved in the space even longer; its NBFC, recently renamed to Altico Capital India, was founded in 2004 and is targeted at real estate project finance. It raised a $300 million round of funding last year, led by Clearwater.

Everstone Capital is one of the most recent entrants to the space, creating IndoStar Capital Finance in 2011. IndoStar provides financing to corporate customer, aiming to meet unique or unusual needs that would not be met by financial products provided by traditional banks.

"There were different types of end users for which loans would be required, which a typical bank may not have considered because, typically, banks would have a very cookie-cutter lending product," says Dhanpal Jhaveri, managing partner for private equity at Everstone. "Given that these would be specialized, custom solution-based loan programs, borrowers would find it easier to come to an NBFC like ours than to go to a traditional banker."

The GP also benefited from a looser regulatory environment allowing 100% foreign ownership in NBFCs, unlike traditional banks. This allowed Everstone to bring in additional partners such as specialist emerging markets investor Ashmore Group and Goldman Sachs.

While the financial returns provided by NBFCs were an attractive enough reason for their early PE backers, as the industry has developed newer models are drawing in groups that were previously inactive in the industry. For example, CDC Group, the UK development finance institution, has shown a growing interest in NBFCs over the last several years.

CDC already had exposure to the industry through its fund commitments, but began to pursue direct deals in 2013 as a means of promoting its financial inclusion goals for India. The move was in part driven by confidence in the Reserve Bank of India's (RBI) response to the global financial crisis, which involved putting in place stronger nationwide regulations such as interest rate caps and limits on loans per borrower.

CDC has committed capital to several MFIs, selecting Janalakshmi Financial Services, Equitas, Ujjivan and Utkarsh for their resilience in the new environment. MFIs provide financial services to low-income populations - typically loans of up to INR20,000 to start a business - although a number have applied for NBFC status in order to gain access to funding from banks.

"We felt like they were very focused on helping that bottom half of the pyramid and the financially excluded, but they were quick to adapt in order to be profitable in the new regime, meaning they diversified their product space," says Maria Largey, director of financial institutions at CDC. "Equitas, for example, very quickly went into affordable housing and vehicle finance. They also increased or improved their operating expense ratios by making more efficient processes and systems."

Other development-oriented investors are attracted to the sector-specific approach among NBFCs. For example, while Kaizen had no involvement in NBFCs before its investment in Varthana, the GP is now looking for additional lending institutions that share its focus on education. IFC, which promotes the development goals of its parent, the World Bank, has also committed to more narrowly focused institutions; not only student lender Avanse, but also home finance provider Repco.

These financial inclusion and development goals are shared by India's government and regulators, which have also shown interest in promoting NBFCs as alternatives to the country's banks. First and foremost, the advantage of these institutions in catering to SME borrowers passed over by the banks holds out the potential to improve employment and development in the country's rural areas and lower-tier cities.

Another impetus for the government and RBI to promote NBFCs is to relieve pressure on traditional banks, whose volume of nonperforming assets is reaching worrying heights. NBFCs can provide an avenue for borrowing that would otherwise fall either on the already overstressed banks or on the unregulated shadow lending sector.

"I don't see how NBFCs' share is ever going to come down in the Indian context, considering how relevant they are at this point in time and given the situation of Indian banks, more importantly," says Sanjeev Krishan, executive director for private equity at PwC. "I think the government has been doing a whole lot to encourage the sector, and I think they're very cognizant of that."

This combination of policy support and low credit penetration - overall and for NBFCs in particular -should sustain the momentum already present in the industry. BCJ projects a constant annual growth rate of 20-27% through the next four years, with NBFC credit reaching as much as INR39 trillion by 2020 - 33% of India's GDP.

Evolution to come

As NBFCs continue to expand their share of the market, industry players expect continued evolution of their business models. The sector-focused approach pursued by the likes of Varthana is seen as having great potential as more entrepreneurs from a wider variety of backgrounds are drawn to high returns available. These institutions need not necessarily be independent - Shriram Commercial Vehicle Finance, part of the Shriram conglomerate, was set up to lend specifically to owners of small freight companies with fleets of only a few vehicles.

"A typical bank will find that extremely cumbersome; they'd rather chase a bigger fish where they can lend large checks and larger amounts," says Everstone's Jhaveri. "So they leave a lot of such business to NBFCs, which are willing to sit with the borrower and agree a proper EMI-based borrowing program - a lot of it will be within the trucking community."

It also hoped that government support for the industry will remain strong as the contribution of NBFCs to economic development in multiple sectors becomes clearer. Current measures aimed at NBFCs include the creation of payment bank licenses, which allow the holders to offer limited banking services and small savings accounts. Several PE-backed institutions have received approval for these licenses, including Kedaara-backed Au Financiers and CDC-backed Ujjivan.

Additional regulatory moves desired by PE investors include the removal of restrictions on partly foreign-owned NBFCs, which are currently subject to a cap on the number of subsidiaries they can open and higher capital requirements to do so than fully foreign-owned institutions. Regulators could also streamline the licensing process to allow faster entry into the market.

These measures would represent minor improvements to an already investor-friendly environment. Most private equity firms active in the space are happy with how it has developed and look forward to further relaxation of the regulatory norms as the industry, and its participants, become more sophisticated.

"When we were looking at making direct investments, one big confidence booster we got was that the regulator seemed invested in making sure that the sector worked," says CDC's Largey. "Similarly now, we are very encouraged by the continued commitment toward financial inclusion and NBFCs. We think that the regulator will do what it can in their power to help continue to support the segment, and that definitely gives us confidence."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.