China VC and US regulation: Defensive positions

Chinese venture capital firms and strategic investors have found their path to US tech start-ups barred by new regulations. It is possible to find a way around, but it requires compromise

Of the $124 million raised to date by Indian social networking and content-sharing platform ShareChat, more than $100 million has come from Chinese investors. Shunwei Capital led the company's Series C towards the end of last year, with participation from Morningside Venture Capital and mobile phone maker Xiaomi, among others.

To William Bao Bean, a partner at SOSV, it is evidence of how offshore Chinese capital has shifted focus. The US used to be the go-to place for deals that complemented a China strategy, but the regulatory environment is now unwelcoming, and investment activity is plummeting. That capital needs to find a new home, so VCs are doubling down on emerging markets within Asia.

"Everyone knows the US is pretty much dead for those guys right now. Perception is more important than reality, and the perception is that Chinese capital could kill deals," says Bean, an early investor in ShareChat. "There was already an upswing in venture in Southeast Asia and South Asia. Now they are getting another tailwind from US dollar-denominated Chinese investment coming south."

SOSV runs six accelerator programs, of which two – Chinaccelerator and hardware-focused HAX – have bases in China. Contrary to claims made by a US Department of Defense-backed organization last year, it is not a Chinese venture capital firm. It isn't headquartered in China, it doesn't raise money from Chinese LPs, and its investment activity in the country is minimal. The accelerator programs may help global start-ups enter China, but SOSV considers itself American.

This distinction is important because it goes to the heart of why Chinese capital is being shut out of swathes of the US technology sector. In the past 12 months, minority VC deals have been drawn into the regulatory remit of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), which was previously restricted to change-of-control transactions. Start-ups are asking more questions as to who their investors are and where their money comes from, fearing that allowing a foreign entity into their cap table might hold up a funding round or even see it retroactively dismantled.

"It has had a chilling effect," says Patrick Loofbourrow, a partner at law firm Cooley. "In the past, you would see an Asian investor the same as a US investor, although you would focus more on their potential value-add and strategic benefits. You still consider those issues now, but you are also thinking about whether they might be deemed a foreign investor or whether other investors will have concerns if they are included. Go back a year or two and the thought process wasn't as acute."

Pulling back

The new rules, driven by the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), which was introduced in August of last year, currently exist as a pilot program. They are described as rife with ambiguity, which has led to widespread uncertainty and the unnecessary cancellation of deals. Some investors are addressing the issue upfront, including CFIUS in term sheets. Others are scaling back their US presence.

The Defense Innovation Unit report cited seven firms as examples of active Chinese investors in the US (though several, like SOSV, dispute the designation): WestSummit Capital, Westlake Ventures, GGV Capital, GSR Ventures, ZGC Capital, Hax, and Sinovation Ventures. ZGC Capital and Sinovation are reducing or reevaluating their activities in the US. The latter has shuttered its operation, industry sources say. Another firm, Danhua Capital, was singled out late last year by the US Trade Representative as a VC with strong Chinese backing. It is reportedly struggling to access US deals.

Chinese strategic investors have also been impacted. A host of groups have established footholds in Silicon Valley in recent years, from Baidu, Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings to Fosun Group, Qihoo 360 and Gome. These teams are now diminished, if not defunct. A source close to Alibaba Strategic Investment told AVCJ that the unit had three professionals in the US and was unsure how they would remain occupied. Most strategic players are now prioritizing other geographies.

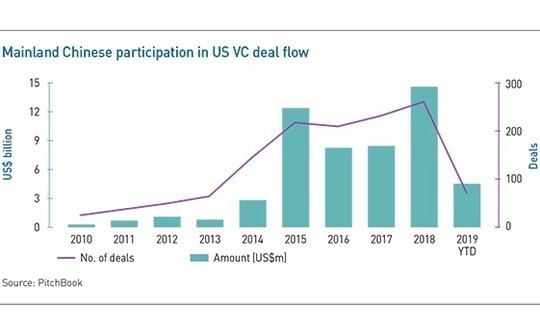

Overall, though, the impact of this dwindling sentiment is plain to see in the investment data. Mainland Chinese investors participated in a record 259 US venture deals in 2018 with an aggregate value of $14.5 billion, according to Pitchbook. This fell to $4.5 billion across 71 transactions in the first half of this year. Corporates accounted for more than one-quarter of the dollar value in 2018, followed by private equity on 4% and corporate VC on 3%.

"If, as a start-up looking for venture funding, my technology fell within the categories defined by FIRRMA, I would think twice about taking Chinese money. There have been situations in which companies have brought in Chinese anchor investors and it has impacted their ability to get government contracts or regulatory clearance wasn't obtained until after an investment closed and the government has ordered a divestment," says Catherine Pan-Giordano, a partner with US-based law firm Dorsey. "Companies could end up in very messy situations."

She adds that this appears to be the prevailing view among many start-ups in Silicon Valley, whether they are involved in overtly sensitive areas such as semiconductors and artificial intelligence or simply run apps that collect users' personal data. The National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) also preached caution when updating its model legal documents earlier this year. The association is said to have approached it "as if CFIUS were interpreting the rules in the most expansive way."

Challenging agenda

The pilot FIRRMA program focuses on 27 industries in which technologies are developed for military use, for civilian-military dual-use and subject to export controls, or for nuclear energy. There is also a handy catch-all that covers areas that have evolved so quickly regulation has yet to catch up. If a technology is designated "emerging and foundational" as part of a regular US inter-agency review process, the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA) can be used to restrict foreign access.

While FIRRMA is not specific to China, industry participants observe there is considerable alignment between the 27 and those outlined in the Made in China 2025 plan. This development blueprint was unveiled by Beijing in 2015 with a view to establishing the country as a high-end manufacturing powerhouse. It envisages China controlling a larger portion of the technology value chain and is widely credited with alerting the US to the potential threat to its status as a global innovation hub.

Many of the FIRRMA industries are irrelevant to venture capital investors: think aircraft manufacturing, guided missiles, nuclear power, petrochemicals, and aluminum production. Others, however, may fall firmly within start-up territory. Computer storage devices, batteries, wireless communications equipment, nanotech, biotech, and semiconductors all appear on the list.

Any foreign participation in a qualifying deal must be disclosed to CFIUS at least 45 days prior to the completion of the transaction. Failure to do so may result in a fine equal to the value of the investment. A short-form filing receives a response within 30 days: either a green light, a request for further information, or unilateral review if the parties are uncooperative. There is also the option of submitting a long-form filing, typically for more complex deals that require a lengthier review.

An in-demand start-up raising a Series B or C round might decide it simply isn't worth waiting around for a Chinese investor to win approval. "The short-form filing process under the pilot program, in theory, gets you clearance in 30-45 days, but very few transactions have actually been cleared in that period," says Christian Davis a partner at law firm Akin Gump. "Most of the time it takes 3-4 months. This deters investors from going through CFIUS and can prevent deals from happening."

The only exemption is for passive investments. In these instances, the foreign party must have no representation on the board or observer or appointee rights, no involvement in high-level decision making within the company, and no access to technical information unavailable to the general public. A foreign investor participating in a US-managed fund as an LP – with no role on the advisory committee, no right to influence investment decisions, and no say over the retention and compensation of the fund manager – is also considered passive.

Yet fund investments are one example of how the ambiguity of FIRRMA comes into play. For example, if a US-domiciled fund has as its general partner a US entity that is managed by two Americans and one Canadian, it is unclear whether investments could trigger mandatory filing rules on the basis that a foreign person – the Canadian – has control. "CFIUS has not clarified the rules in that regard. Neither has CFIUS answered questions as to whether an offshore fund managed entirely by US individuals would trigger mandatory filing," says Stephen Heifetz, a partner a Wilson Sonsini.

For deals that fall outside the pilot program, 10% is generally considered the threshold below which an equity interest is considered passive. However, CFIUS has clarified its position on two previously gray areas. First, the implied equity interest of acquired shares plus convertible voting rights can be factored into review decisions. Second, a deal in which a foreign investor takes a 10% equity interest but also receives governance rights to appoint the CEO and CTO would be subject to review. CFIUS retains the right to retroactively unwind transactions that are not disclosed and prompt concerns.

Pan-Giordano notes that she has worked with Chinese investors that didn't seek board seats or any meaningful influence over a target company's operations. But they did want something else. It is not unusual for strategic players to demand a commercial alliance – such as Chinese licensing or distribution rights to a technology – in return for their capital. Such arrangements may fall foul of efforts to capture deals that deliver control without exceeding a certain level of equity ownership.

"For investments where filing is mandatory for a change in control, the term control is now more liberally interpreted," she says. "What is control? It is influence over management and decision making. If you tie up the technology through exclusive contractual rights to licensing and distribution, even if you are below 10% you might not be completely safe."

In addition, transactions that involve exclusive licensing of technology to China might be subject to export restrictions. Several industry participants observe that biotech, while part of the 27, hasn't been hit hard by FIRRMA because the companies are not designing critical technology. Others warn that obstacles are wide-ranging. "There is a difference between CFIUS and export controls," says James Huang, managing partner of Panacea, a China-focused healthcare VC firm that invests globally. "There are ever more US government restrictions on what can be licensed out."

The big picture

Licensing molecules from established US pharmaceutical companies for drug development locally is a mainstay of China's biotech industry. However, this practice came under threat last year when the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the primary body responsible for public health research in the US, encouraged members to brief the FBI on any attempts by foreign governments to influence their work. Chinese scientists claimed their country was being targeted.

Indeed, efforts to warn US companies about the risks of China's insatiable appetite for intellectual property (IP) appear to be widespread. In addition to the FBI stepping up educational efforts on how start-ups can protect against IP theft, a research report published by the US-China Economic Security Review Commission in May outlined how Chinese companies facilitate technology transfer from the US, through legal and coercive or covert means. Venture capital was one of the channels cited.

"Although Chinese companies are not the only foreign firms seeking to acquire US technology, the Chinese case is unique because the Chinese Communist Party has prioritized technology transfer as a matter of policy and provides direct and indirect support to companies engaging in these anticompetitive activities. Chinese acquisition attempts frequently target advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and virtual reality, which are still in the early stages of development but could provide dual military and civilian capabilities in the future," it says.

This gives context to concerns expressed by industry advisors about exaggerated responses to FIRRMA based on information that offers an incomplete or overly generalist assessment of the policy environment and the fine detail. "The bigger impact of FIRRMA has been the noise around it that has deterred parties on both sides rather than the rules themselves," explains Davis of Akin Gump. "If you dig into the details you can find ways to invest in areas where you aren't going to be restricted."

In some cases, investors looking to do the CFIUS analysis first, complete due diligence around it and then structure the agreement appropriately. The emphasis is on eliminating the need to file with CFIUS, even if this comes at the expense of investor rights. "We are continuing to advise lots of Chinese investors, but the more cautious among them are making passive investments that are not likely to be subject to CFIUS jurisdiction," says Heifetz of Wilson Sonsini.

As a longer-term measure, some venture capital firms are expected to review their fund structures to minimize the risk of being classified as foreign investors. This may mean not only changes in domicile, but also a cleansing of GP-LP relationships so that a Chinese strategic investor doesn't own a stake in the GP, have representation on the investment committee, or staff seconded to the fund. Beyond that, they might ensure that Chinese LPs do not account for most of the corpus.

These are complex adjustments, but they reflect a recognition of a new normal and the need to adapt if capital is to continue flowing to start-ups. Final implementation guidelines for FIRRMA must be issued by February 2020, and no one is predicting compliance requirements to slacken. "The US government has lots of levers and there are people in the current administration who view it as their mandate to sever economic ties between the US and China," says one US-based lawyer. "CFIUS isn't the only lever available to them, but it's one of them and it's having an effect."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.