China M&A: Outbound 2.0

Following the issuance of regulatory guidance, the aggression and opportunism that once characterized corporate China’s approach to overseas M&A will be replaced by moderation and consideration

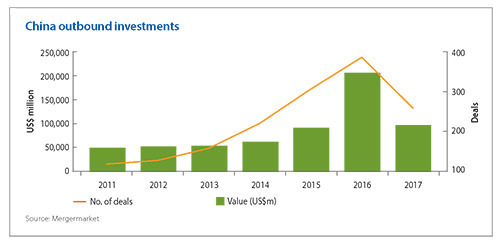

Does Syngenta represent a high-water mark for Chinese outbound investment? The $43 billion acquisition of the Swiss agribusiness giant by China National Chemical Corporation (ChemChina) capped a record year for Chinese companies, with $204.1 billion committed to 280 offshore deals. However, the momentum has proved impossible to sustain in the face of restrictions on capital outflows.

The government clampdown reflected concerns that domestic corporates had become too aggressive in their deal-making – going after assets from football clubs to movie studios that had little in common with their core business and piling transactions high with debt provided by Chinese banks. Outbound investment duly slumped to $96.2 billion for the year through September from $164.5 billion for the same period in 2016. The number of announced deals fell to 258 from 291, according to Mergermarket.

In August, the State Council published new guidance on outbound M&A, reinforcing the desire to stop irrational transactions while offering insights into the kinds of deals that would be favored. There is now greater regulatory clarity, but the heights of 2016 are unlikely to be surpassed in the near term due to closer government scrutiny in China and increased wariness of Chinese investors overseas.

"Chinese overseas investment is entering a new norm compared to that of 2016. Investors will be more rational and targeted sectors will be more diversified and balanced." says Junwei Chen, CEO of Harvest Technology Investment, a cross-border PE firm under Harvest Fund Management. Previously, Chen was responsible for six outbound deals completed by ChemChina.

"The Chinese companies going global phenomenon is still at an early stage. Many state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private enterprises have yet to become truly multinational organizations in terms of technology, brand, management and channels of distribution. Outbound M&A and the effective post integration can create value through the internationalization process."

Outflow angst

China's key regulators applied the brakes in the second half of last year with a slew measures allowing for increased scrutiny of investors looking to exchange renminbi for foreign currency. They paid particular attention to large investments that had little relevance to the investor's major business areas, any transaction involving real estate or entertainment, and deals led by renminbi-denominated funds. Investors were also asked to justify their transactions in terms of valuations, financing arrangements, and expected benefits. The bottom line was that getting approval became much tougher.

In June, regulators intensified their focus on four of China's most prolific deal-makers, ordering banks to provide information on their exposure to outbound investments completed by Anbang Insurance Group, Fosun Group, HNA Group and Wanda Group. "Previously, the overseas branches of Chinese banks provided debt financing based on onshore guarantees – pledges of real estate or other assets – from the acquirers. This kind of structure is now subject to more stringent regulatory control," one banker says.

The guidance document released in August formalized the government's approach by dividing transactions into three categories: encouraged, restricted and prohibited. Restricted sectors such as real estate and hotels, sports, and entertainment are likely to see less activity.

"What the Chinese government wants to do is to be more selective and risk-averse towards outbound investments. They don't want to see Chinese entities exposed to high levels of financial risk. By blocking investments in assets like real estate, hotels and movie studios, the rationale appears to be it's hard to justify that they are of benefit to the Chinese economy," says John Gu, a partner at KPMG China.

The guidance document also seeks to curtail the activities of outbound investment funds. Previously, Chinese corporates would source capital from domestic investors for blind pool structures that pursued deals in certain sectors. Regulators suspected these vehicles were surreptitiously being used for speculative real estate investments, so now they are subject to approval on a transaction-by-transaction basis.

The areas in which investment is encouraged clearly dovetail with government policy: foreign technology and manufacturing expertise that facilitate upgrades in China's traditional industries as well as projects that relate to the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative. While outbound deals currently take as long as six months to gain approval, OBOR investments have been known to receive clearance in less than half that time.

"OBOR is still a very early-stage initiative, with a specific focus on infrastructure and logistics, but no other government has put forward an ambition on this scale," says Harsha Basnayake, a managing partner in EY's Asia transaction advisory services practice. "Having said that, I wouldn't expect OBOR to spark an M&A spree because most infrastructure deals are greenfield projects that will not take off immediately."

China's investments in OBOR regions – which stretch from China to Europe and Africa – totaled $25.9 billion last year, with majority of the transactions handled by state-sponsored groups, according to Mergermarket. Various regulators have offered support. For example, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) anchored the Silk Road Fund, which received initial capital of $10 billion towards a target of $40 billion. It has also supported programs run by CIC International, China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China (Chexim) that back OBOR-related investment funds.

The China-Eurasian Economic Cooperation Fund (CEEF), which is looking to raise $5 billion, was among those to receive an LP commitment from Chexim. CEEF currently focuses on direct investments but it wants to back smaller funds in OBOR markets as well.

"Developed markets like the US and Europe aren't our focus. We target emerging economies – such as Russia, Southeast Asia and India – where they welcome foreign investments. We have the flexibility to invest in a broad range of sectors, primarily through minority stakes, and also join large consortium deals led by Chinese players. Through these investments, we hope to facilitate closer cooperation between Chinese enterprises and companies in Central Asia," says Honghui Sun, CIO at CEEF.

In a bind

While SOEs are encouraged to make OBOR-related investments, elsewhere the capital control policy has forced them to become more conservative. Some groups have formed a teams to handle inquiries from regulators about outbound deal flow, according to industry participants. SOE boards are now also held directly responsible for the quality of overseas assets their companies want to buy as well as the post-investment performance. As such, they are reluctant to approval international deals.

And whether SOE or private business, acquisitive companies risk falling foul of the blacklist system being developed by the Ministry of Commerce. Those that violate the regulations – for example, by investing in a restricted category without gaining the relevant approvals – will be added to the list, which means it will be harder for them to win regulatory backing for future investments.

"Stringent regulations and deal approval processes will probably exist in the market for at least 6-12 months. People should just follow the guidance. Once the approval comes through, they can think of more innovative ways to raise offshore capital, such as partnering with financial investors or raising capital from state-backed funds for co-investment deals," says Zhiping Zhou, founding partner at cross-border M&A advisory firm RJ Capital.

As for Anbang, Fosun, HNA and Wanda, there is a little evidence to suggest they will return to their former profligacy. Other smaller players, although they have limited experience of overseas acquisitions, should be able to make up some of the shortfall as they use M&A to expand into new markets and acquire advanced technologies. Artificial intelligence, robotics, biotechnology and automobile components are all of interest – and they fall under the encouraged category.

"If you look at the Chinese economy, the largest companies still tend to be SOEs, so that they have more capacity to execute mega deals. But privately-owned businesses are expected to be more active than the SOEs by number of transactions," says Philip Li, a partner at law firm Freshfields. "Private companies aren't likely to target multi-billion-dollar deals, but they could spend up to $1 billion on a strategic asset."

However, these companies will face greater regulatory scrutiny overseas as well as at home, with foreign governments move to restrict the flow of critical technology and knowhow into Chinese hands. Midea's takeover of German robotics manufacturer Kura won government approval but sparked intense debate in Germany while the proposed acquisition of US-based Lattice Semiconductor by Canyon Bridge – a private equity firm backed by Chinese LPs – was blocked for reasons of national security.

At the same time, foreign companies have also raised the bar for Chinese bidders, citing the uncertain approvals process. For highly attractive assets, break fees that normally amount to 5% of the total deal size increased to 10% last year for transactions involving Chinese companies. Some of these groups ended up abandoning acquisitions because they were not confident of winning regulatory approval and getting the capital offshore in time to settle payment.

"The Chinese government has said several times over the last few months that it still supports outbound investments, but the damage has already been done," another banker observes. "Western sellers nowadays do not welcome Chinese buyers into bidding processes – they may want them in there to help push up the price but they don't want them to be among the final bidders. The perception among Western companies is that the Chinese buyers can't get the money together."

The PE angle

Plenty of transactions currently in the pipeline may fall through, but at the same time this creates opportunities for another type of capital provider: private equity. GPs with offshore funds are not subject to the same restrictions as groups with renminbi-denominated assets, so they can work with these Chinese counterparts and partially underwrite investments as well as utilizing their execution expertise.

A number of deals of this nature have been announced recently. In May, China Renaissance Capital Investment (CRCI) teamed up with Chinese industrial group Zhengzhou Coal Mining Machinery (ZMJ) to buy a starter and generator manufacturing business from German multinational Robert Bosch. Last month, CITIC Private Equity announced it would acquire Canada-based Therapure Biopharma's contract development and manufacturing business in conjunction with 3SBio.

"Having US dollar PE firms as partners will effectively help Chinese corporates reduce the amount of money they need to convert from renminbi into foreign currency. Hopefully, this means an easier process and shorter timeline to complete the deals," says Li of Freshfields.

These deals often feature a pre-agreed exit mechanism, including the Chinese corporate buying out the PE firm's stake in the target. In some situations, the GP is able to swap its interest for shares in a listed unit of the Chinese corporate, thereby guaranteeing liquidity. In the Therapure deal, for example, CITIC PE took a 49% interest in the joint venture acquisition vehicle, with the rest held by 3SBio. It has a put option under which it can sell all or part of its interest in the joint venture to 3SBio after four years.

The challenge for PE investors is identifying a reliable partner. Before entering into any agreement, they must evaluate the Chinese corporate's domestic credibility, its ability to bring capital offshore, and whether it possesses the executional capabilities to get deals done.

"Private equity firms that play the co-investor or bridge financing role will be very selective in participating in these outbound transactions because they don't want to get into a situation where they finance the deal but they can't pull out if the Chinese investor's foreign exchange approval doesn't come," says KPMG's Gu. "In that sense, certain SOEs may be a better partner if they have overseas subsidiaries. The PE firms can help structure deals using these offshore units instead of working with pure local players that have no offshore assets."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.