India's goods and services tax: A fair fight

While India’s new goods and services tax regime has caused temporary dislocation, private equity players are confident that their portfolio companies are set for long-term success

When India's goods and services tax (GST) came into effect last month, Ginger Hotels watched with satisfaction and relief. The tax, part of a raft of regulatory and legislative initiatives aimed at modernizing the country's economy, looks set to put India's largest economy hotel chain on a more even footing with some of its most persistent and frustrating competitors.

"Historically Ginger has competed against mom and pop operators who probably didn't declare their true income and didn't pay adequate taxes, and a lot of profit was driven by undeclared payments," says Bobby Pauly, a partner at Tata Capital, which invested in Ginger in 2011. "But with more transparency coming in and a level playing field being created we're seeing greater structural benefit for organized players in this industry."

Tata is one of many Indian private equity players that have looked forward to the roll-out of the long-awaited GST. With the policy expected to affect every sector, most expect it to have as big an impact as last year's demonetization initiative. While that change arrived with no warning, investors have had years to consider the effects of GST. Most concluded they had little to lose and much to gain.

While India needs time to adjust to the new tax, enthusiasm for the GST is generally high among GPs, who believe it can give their investees a critical edge. Companies will need to adopt strong financial reporting and transparency standards to comply with the new tax regime, and PE firms can be helpful partners when striving for this level of performance.

"GST helps level the playing field between the organized and unorganized sectors and emphasizes compliance within a structured and uniform tax framework," says Dhanpal Jhaveri, managing partner for private equity at the Everstone Group. "It's arguably the biggest reform India has seen since its economic liberalization in 1991."

Long time coming

As might be expected with such a fundamental overhaul, GST has endured a long gestation. The concept was first recommended by a government task force in 2003 as a replacement for the cumbersome tax system. Two years later the government proposed to introduce GST by 2010 – yet the required constitutional amendment was not introduced until 2011, and it finally passed four years after that.

The amendment's passage, and the intent of the Modi government to implement badly needed reforms, meant GST became more of a reality in investors' minds. For example, Tata Capital's 2015 investment in TVS Logistics, the transport-focused subsidiary of TVS Group, was based on the assumption that GST would take effect soon. But the two years between passage and implementation struck many observers as unusually quick by Indian government standards.

"GST has been long overdue, but while the government made it clear that they wanted to start it on July 1, very few people expected that it would actually happen then," says Tata's Pauly. "I think it's been a bold move, but also a good move in retrospect, for it to be implemented within this time frame."

Though many economic reforms arrive with sweeping claims of their economic impact, GST is one of the few that seems likely to fit the bill. The tax overturns India's entire system of municipal, state and national taxes, replacing them all with a single levy paid to one collection center. Companies are expected to see their filing times and costs drop considerably.

Compared to the previous system, GST is relatively simple. Goods and services are taxed at different rates by category, ranging from zero for foods such as grains, milk and salt and services such as education and housing through 28% for air conditioners, refrigerators, gambling and luxury hotels.

The tax is paid at each point of sale in the supply chain, with each buyer entitled to a rebate of the tax paid when the seller acquired the item earlier. Taxes are collected on the state level, with each state delivering the appropriate amount to the national government (which varies depending on whether the sale is made within a single state or between states).

In the case of a refrigerator, the manufacturer might sell the product to a distributor for INR500, with the distributor paying INR140 in GST. The distributor could then sell the product to a retailer for INR1,000, with the retailer paying INR280 in tax and subsequently rebated for the tax previously paid by the distributor so that its final payment comes to INR140. Each participant in the chain reports the tax paid through a central server maintained by the government.

For business, the new method has the advantage of being convenient and easy to understand – but from the government's perspective what is even more attractive is that it is self-enforcing. Any supplier in the chain that does not register and pay GST cannot be rebated for the tax paid lower down on the ladder, and neither can the next buyer on the chain, which would need to pay the full GST.

"No buyer would procure from this supplier, because for every buyer the products would become more expensive," says Nitish Poddar, a partner at KPMG India. "That supplier will therefore be marginalized. Companies would rather buy the same product from a GST-registered supplier so they can save on the tax."

While all sectors are expected to benefit from the measure, logistics could make huge gains because one side effect of GST is to eliminate almost all interstate taxes, thereby dramatically reducing the cost and time required to deliver goods. Trucks will no longer need to stop at every state border for inspection and tax assessment, and companies will not need to maintain warehouses in multiple states to avoid interstate tariffs. Tata Capital-backed TVS Logistics is already leveraging this potential.

"In today's GST environment, TVS Logistics can say to customers, ‘I'm actually delivering for you in four states – why don't I provide my services for you on an all-India basis, because I'm best placed to do this in terms of consolidating your warehousing and your distribution points,'" says Tata's Pauly. "That's a conversation we've started having with our customers, and we've had a very good rate of success so far."

Teething problems

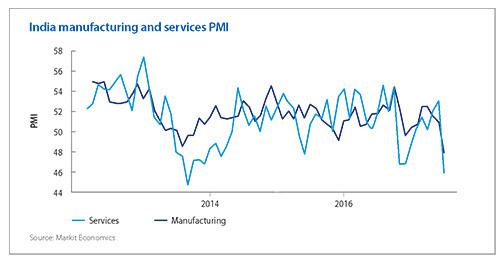

Economic data suggest that the introduction of GST did cause some dislocation. According to Markit Economics, for the month of July the purchasing managers index (PMI) for both the manufacturing and the services sectors dropped sharply, to 47.9 and 45.9 respectively. In the case of the services PMI it was the biggest fall since September 2013, with output and new orders declining for the first time since January this year.

Adjustment issues related to GST include concerns from distributors about tax filing deadlines – under the old system most taxes were paid by sellers. Under the new system, with buyers required to pay, distributors are reluctant to stockpile items the way they are used to, meaning that manufacturers have faced a downturn in orders.

"With GST the moment you buy something you have to pay the tax in the same month," says KPMG's Poddar. "The distributors don't want to hamper their cash flows by buying more products, so there have been situations where people have taken a step back to see what happens before taking the next decision."

Despite these teething issues, industry observers are confident that India's economy will adjust quickly and be all the stronger once companies have registered with the new tax regime and adopted financial reporting standards to ensure compliance.

PE-backed companies are seen as having a leg up on this process, since formalization is among the most immediate areas for improvement targeted by firms. Indeed, many managers feel that their insistence on adherence to high governance standards puts their portfolio companies at a disadvantage compared to their competitors in the informal economy. The new tax regime, among other reforms, is expected to finally put all players on the same footing.

"You might not normally expect a business like pest control to be highly informal, but in India there are a lot of informal players who provide those services because the entry barriers can be fairly low," says Srikrishna Dwaram, a partner at True North, referring to the firm's portfolio company HiCare. "Those players will get impacted by demonetization combined with GST, while the market share of the formal players will increase, so we stand to benefit."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.