India demonetization: After the storm

In the aftermath of India’s demonetization policy, the direst predictions have failed to materialize. But the experience has also shown how little power PE firms have in some situations

For Srikrishna Dwaram, the timing couldn't have been worse. It was November 2016 and Dwaram, a partner at India Value Fund Advisors (since renamed True North Managers) was putting the final touches on an investment round and restructuring for portfolio company Disha Microfin, a microfinance institution (MFI) targeting lower-income consumers. The deal would help the company achieve final approval for a small finance bank license from the Reserve Bank of India.

Then came the surprise announcement by India's government that INR500 and INR1,000 notes were no longer legal tender, to be replaced immediately by newly designed bills. The move, which came without any warning and is estimated to have affected nearly 90% of the currency in circulation by value, sent shock waves across the Indian economy.

No sector was without concern, but for Disha, whose customers mainly used cash, the move could have been catastrophic. The other potential investors immediately wanted to press pause on the deal – but the deadline for the MFI to finish its small finance bank application was approaching and it wouldn't go through without the investment and restructuring to reduce IVFA's shareholding to the required amount.

"It all turned out well, but it was a fairly stressful period," remembers Dwaram. "We needed to do a lot of thinking at our end and a lot of convincing. There were eight or nine investors in that consortium and we had to bring everybody together on board to be able to do it. Even if one investor fell out of that consortium the deal wouldn't have gone through."

Mixed feelings

The deal sticks in Dwaram's mind as the most difficult situation that True North faced following the demonetization announcement. But in the confusion that reigned six months ago in the policy's immediate aftermath many wondered if far worse consequences could be expected. In hindsight, Dwaram and other GPs say the impact has been much more limited than initially feared.

While investors now largely express relief at the smooth transition and lack of major issues, there is also a recognition that the outcome was in many respects out of their hands. Private equity firms can help to prepare companies for stressful periods in general, but the experience of demonetization shows that sometimes the only option is to hang on and ride out the bumps like everyone else.

For all the shock that greeted demonetization, observers acknowledge in hindsight that some form of jolt had been a long time coming. India has always been heavily reliant on cash: figures from the World Bank show that the currency in circulation in India came to 12.3% of its GDP in 2015, more than in any other country except Japan.

The government saw this cash reliance as an enabler for counterfeiting, tax evasion and political corruption. The INR500 and INR1,000 notes were a particular problem, together accounting for nearly INR15 trillion ($232 billion) in untraceable capital, or about 10% of the pre-demonetization GDP.

Despite the inevitable economic impact, the government went ahead with the initiative, showing considerable discipline in keeping it under wraps. Investors received no warning until the day of the announcement that notes held by every class of society were about to be rendered worthless.

"There wasn't even an hour of notification, there was no prior information. It just happened," says Vivek Soni, a partner with the private equity group at KPMG India. "The beauty of the whole thing was in its surprise, so there was nobody who had advance information this was happening."

Indeed, though the lack of warning left many Indians scrambling to react, investors also acknowledge that taking the old notes out of circulation immediately was the best way to accomplish the government's goals. Otherwise the counterfeiters and tax evaders that it was trying to cripple would be able to exchange their old notes and keep their ill-gotten gains.

Crisis management

But this understanding did little to help with the dilemma faced by India's PE community: how to gauge the effect of the policy on their portfolio companies, and to counteract any negative impact. The simple fact was that due to the unprecedented nature of the government's move there was little previous history by which investors could judge the effects. The industry was largely flying blind.

"It really came as a bolt from the blue because there was no warning, and nobody was expecting anything so draconian," says Sanjeev Krishan, India private equity leader with PwC. "The question has been whether we can expect anything similar in India which is unplanned. And that's something which has, I think, impacted investors for a fair bit of time."

Businesses that deal with large amounts of cash were naturally expected to be hardest and most immediately hit, with concern focusing on consumer-oriented companies. While many managers report inconvenience for B2C businesses, there is actually no indication of major hardships or crises faced by these companies in the aftermath of demonetization. Krishan says the worst he has heard in this regard was that some GPs had to push back planned exits to the next quarter to see what the fallout of the announcement would be.

Economic statistics reflect this reported mild impact. Rabobank calculated the purchasing managers' index in India dropped sharply at the end of 2016, but showed a large rebound in the first months of 2017. Vehicle sales experienced a similar recovery; though sales as of the most recent report were still significantly below the August level, the speed of the turnaround suggests that purchases were delayed rather than canceled.

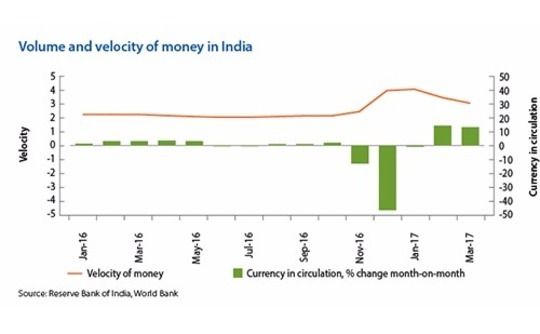

Overall GDP continued to grow at the prior rate as well. World Bank calculations show the velocity of money in India – a measurement of the purchasing power of money defined as quarterly GDP divided by currency in circulation – jumped significantly from its formerly stable rate as currency was removed and has remained above average as it returned. This suggests that economic activity remained stable in the low-cash interim.

"In normal times, it may be difficult to know who is who. During demonetization, however, most customers requesting to buy on credit would be expected to fall under the ‘illiquid' category as it was widely known that people had difficulty accessing cash. This made the provision of this type of small, informal credit more likely," says Gil Sander, senior India economist at the World Bank.

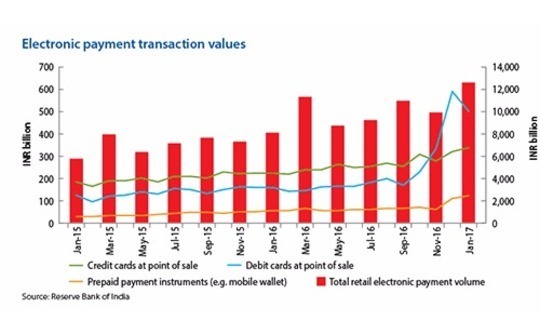

Another major factor in the quick rebound was the adoption of non-cash payment methods. If any industry emerged as a clear winner in the demonetization saga, it was probably digital payments. According to the Reserve Bank of India, use of electronic payment methods in general grew following the announcement, most significantly debit cards at point of transaction, which more than tripled in value from September to December 2016.

"The expectation is that the use of non-cash payments will continue to expand at a rapid pace," Sander adds. "However, continued efforts on the infrastructure front – from literacy, to platforms in different languages, to access to cell phones and the internet – will be required to ensure this transformation is inclusive."

Cashless society

Such investment is likely, considering that growth in non-cash payments was actually a goal of the demonetization policy. Using bank accounts, credit cards, mobile wallets or other regulated instruments for payments renders transactions more traceable and consequently taxable than cash purchases, which can be hidden from the government more easily. Policy makers were so intent on pushing these methods that they reportedly resorted to measures likely to increase the annoyance of cash users.

"The government deliberately underfilled the ATMs, because it wanted to force the average middle class and other people who would take out cash and give it to other people or vendors to say, ‘It's inconvenient for us to go and wait and collect money from the ATM. Give us your bank account number and we'll just transfer the money,'" says KPMG's Soni. "It wanted people to change their habits, and to some extent it has succeeded."

The government's willingness to inconvenience its citizens for the sake of progress did have limits. Farmers, for instance, were protected to some extent because they could continue to use the old notes to buy seeds through the end of the year, and the old notes were also accepted for fuel purchases until December.

But other players connected to these industries have not been so sheltered. In the case of an agriculture-focused non-banking financial company (NBFC) backed by True North, the timing of the announcement had a major impact on its business, which involved providing loans to farmers to store their produce in warehouses that the company contracted with.

"It was well known ahead of time that it was going to be a very good year in terms of the harvest, so in anticipation of a great season we had contracted a lot of warehouses. Then demonetization happened," True North's Dwaram says. "Because there was no cash available in the market nothing came into the market, so we had warehouses, but no produce to store."

In this case, the firm found it actually had very little leverage to mitigate the consequences. The announcement late in the year, with no warning, meant that the NBFC had no chance to formulate a response or renegotiate the contracts. It was nobody's fault, but all the company and True North could do was ride out the loss and hope to recover when the next harvest came.

The business has returned to normal following another good harvest early this year, but the experience illustrates the limitations faced by GPs in responding to the demonetization initiative. Such passive responses tended to be the order of the day, with PE backers mainly having to trust in the strength of management teams to be able to weather a temporary setback. A manager at one GP said its response was mainly limited to arranging the availability of new notes for portfolio companies so that they could make payments during periods of low supply in the first few months.

Long-term gains?

Despite the initial anxiety around demonetization and the private equity community's relatively small contribution to the recovery, investors largely express satisfaction with the measure and its outcome. The knowledge that the cash shortfall would be temporary and quickly resolved by the introduction of new notes is one factor in this reaction, along with the belief that the initiative would in the long term help move India toward financial inclusion, matching the goals that many of the country's investors share.

"We have almost as a rule invested in businesses that gain through the increasing formalization of the economy," says Gopal Jain, co-founder and managing partner at Gaja Capital. "Demonetization was perhaps the most serious blow in favor of formalization in the last 70 years and in this sense was positive for our portfolio."

In recent months investors have also come to see demonetization in the context of other measures that are expected to bring increased discipline to the Indian economy. The goods and services tax (GST), planned for implementation in July, is the most prominent example, since it will encourage businesses to use formally registered companies – the kind that PE firms tend to back – rather than unlicensed providers, so that they can write off the tax.

More time is needed to judge the ultimate effects of the policy, and some are concerned about the impact of the long-expected GST on top of the unanticipated demonetization. However, for India's PE industry, the aftermath of demonetization appears to be largely business as usual. The value of most of the removed cash has been replaced, meaning cash-reliant businesses have either returned to normal or will in the near future, and the digital payments ecosystem has gained a much-appreciated stimulus.

The reaction has been more wary in other quarters. PwC's Krishan says he has seen a drop in interest from Western investors in recent months due to the lack of warning about demonetization and concerns that the government has opened the door to further unannounced interventions. Japanese and Chinese investors, on the other hand, have reacted largely in the same way as their Indian counterparts, seeing the measure as drastic but necessary due to India's unique circumstances and unlikely to be repeated.

"This is not even an emerging market issue, this is something which can happen in any country or geography that has a significant amount of purchasing power in cash," Krishan adds. "Private equity investors do not always like those kinds of businesses. But if they are investing in some of these geographies, then that's the risk that they agree to carry."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.